Evaluation of the Immigration National Security Screening Program: Executive summary and introduction

Executive summary

Note [redacted] A redacted note appears where sensitive information has been removed in accordance with the Access to Information Act and the Privacy Act.

Evaluation purpose and scope

The evaluation examined the performance (effectiveness and efficiency) of the Immigration National Security Screening (INSS) Program (the Program), between fiscal years (FY) 2014 to 2015 and 2018 to 2019, in accordance with the 2016 Treasury Board Policy on Results. The evaluation was undertaken between and .

Program description

The Program is delivered by the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA)’s National Security Screening Division (NSSD) within the Intelligence and Enforcement (I&E) Branch. The NSSD collaborates with Immigration Refugee and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) and the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) to deliver on the Government of Canada’s security screening objectives. Ultimately, the NSSD helps prevent inadmissible foreign nationals or permanent residents from entering or remaining in Canada, while facilitating the entry of admissible individuals. The IRCC receives and performs an initial assessment of applications for temporary residence (TR) or permanent residence (PR) and refers applicants who potentially pose security concerns to the CBSA and/or CSIS for in-depth security screening. In addition, all refugee applicants who submit their claims at a CBSA or IRCC inland office in Canada, and whose claims are deemed eligible, are referred to the CBSA and/or CSIS for security screening. In its role, the NSSD assesses potential inadmissibility concerns under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA) section 34 (espionage, subversion, terrorism, danger to the security of Canada, membership in an organization that engages in the aforementioned acts, or violence), and/or section 35 (crimes against humanity, war crimes, genocide, sanctions) and/or section 37 (organized criminality). After completing a screening, the NSSD sends an admissibility recommendation to the IRCC, in the case of TR and PR applicants, or notifies the Immigration and Refugees Board (IRB) on the recommendation issuance in the case of refugee claimants. IRCC or the IRB then decides whether to grant the applicant entry to, or permission to remain in, Canada.

Evaluation methodology

Data collection and analysis for this evaluation were conducted between and ; both qualitative and quantitative research methods were used. The evaluation team interviewed stakeholders from the CBSA, IRCC and CSIS, reviewed key documentation, analyzed operational and financial data, and administered surveys to NSSD analysts and IRCC officers.

Evaluation findings

The NSSD is required to provide legally defensible and timely recommendations on the results of their security screening assessments to decision-makers. Between 2014 and 2019, the NSSD delivered legally defensible recommendations. However, most of the time, these recommendations were not issued within the established timelines (i.e. did not meet service standards) as a result of external events such as Operation Syrian Refugee (OSR) and increased irregular migration (IIM), as well as other workload pressures.

The NSSD’s recommendations were well-grounded in legislation. This was evidenced by a low proportion of cases in which applicants challenged the legality of IRCC’s or IRB’s decisions to reject applications or asylum claims based on security grounds. However, the usability of the information contained in the NSSD’s inadmissibility briefs could be improved. NSSD analysts had regular access to legal advice during the evaluation period, although the legal defensibility of their assessments could be strengthened.

In terms of timeliness of recommendations, the NSSD did not meet its related performance target for most of the evaluation period for a number of reasons. Two major events caused significant increases in the NSSD’s workload: OSR in 2015 to 2016 and IIM at the Canada-US border beginning in mid-2017. A major backlog of referrals ensued, which adversely affected the NSSD’s ability to issue timely recommendations. In , after the adoption of a comprehensive suite of backlog reduction measures, the NSSD started meeting service standards again. In addition to OSR and IIM, the steady growth in the number of TR and PR applications submitted to IRCC (amounting to a 70% increase over the 5-year period between FY 2014 to 2015 and 2018 to 2019) led to a corresponding increase in the number of referrals submitted to the NSSD and further added to the increasing workload. By the end of the evaluation period, the NSSD had significantly reduced its backlog. In this regard, the Division’s Surge Capacity Plan could be improved to better support the Agency in the event of sudden surges of referrals in the future.

The NSSD’s performance measurement was relatively limited during the evaluation period; measurements centred primarily on monitoring the Division’s inventory and backlog trends. Certain key performance variables and the Program’s outcomes are yet to be fully defined and/or meaningfully measured. Internal policies and procedures have been enhanced in recent years, but opportunities exist to help ensure analysts are kept fully up-to-date on events of concern around the world. The NSSD provided learning and training opportunities to analysts, particularly upon joining the Division. Analysts would benefit from better access to Privy Council Office (PCO) intelligence-related courses and from further training and/or support in determining inadmissibility related to organized crime.

In response to its rapidly rising workload, the NSSD, in collaboration with CSIS and IRCC, started revising the security screening indicators used by IRCC officers to guide what applications should be referred for in-depth screening. The goal of these revisions was to improve the referrals made by IRCC, by reducing the number of unnecessary referrals and enhancing their quality overall. By , 16 new indicator packages were in place; however, their impact on referral quantity and quality had yet to be determined as of the end of the evaluation period. A number of IRCC missions and CBSA regions submitted a significant proportion of incomplete referrals during the evaluation period, which required follow up by the NSSD and also added to its workload.

Overall, the NSSD, IRCC and CSIS had a good working relationship over the evaluation period; partners felt that roles and responsibilities were clearly defined. The Program would benefit from leveraging the new trilateral Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) to both enshrine the specific tasks fulfilled by each partner and to articulate the interdependencies between key partner activities. Ways to obtain more information and intelligence to support NSSD analysts’ assessments of inadmissibility due to organized criminality should continue to be pursued, such as re-engaging with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) in the federal INSS Program. Additionally, there are opportunities to improve communication and coordination between the NSSD and CBSA regional investigations units in terms of screening refugee claimants, an activity both entities carry out.

In terms of information technology and management, the case management systems used by the NSSD, IRCC and CSIS were not designed to be inter-operable. The lack of interoperability has been a long-standing issue in the Program; nonetheless, NSSD analysts felt they had the information they needed to perform screenings. Throughout the evaluation period, NSSD’s screening activities were largely dependent on manual tasks performed by analysts. Manual work not only limited the processing ability of the Division, but is also more prone to human error. Automation is the future vision of the Program, but is several years away from being fully implemented and has associated risks.

In terms of efficiency, the Division managed to double the number of recommendations issued over the evaluation period. However, these gains were to some extent offset by the decline in the average number of recommendations issued per hour, and by the rise in the average cost per recommendation. According to the NSSD, these trends may be explained by a shift to higher quality and more robust recommendations in recent years, which are typically more time consuming to research and document.

[redacted] Such analysis could assist in further refining the security screening indicators, which, in turn, could result in greater Program effectiveness, by focusing screening on applicants who are most likely to pose a security concern.

Recommendations

The findings of the evaluation led to the following recommendations:

- The VP of I&E should strengthen the measurement of the Program’s performance. This includes:

- revising the logic model to ensure that the immediate and intermediate outcomes fully capture the Program’s intended objectives and include logical flow from one outcome to the other

- revising the key performance indicators (KPIs) to align with the objectives in the revised Logic Model and assist the NSSD’s leadership with performance management accountability and decision-making. The new KPIs should include establishing internal processing times that are independent from service standards communicated to the IRCC

- The VP of I&E should enhance the NSSD’s Surge Capacity Plan, so as to develop additional capacity within CBSA to support a sudden surge in referrals. This includes the consideration of:

- identifying staff within CBSA, including Regional staff, who are able to conduct screenings and who can quickly be deployed on a part-time or full-time basis, and for an extended period if necessary

- providing regular training and refresher training to the above identified staff

- applying quality assurance to security screenings conducted by the above identified staff

- The VP of I&E should advocate for clearer articulation of the objectives of the new thematic indicators and their expected impact on the security screening process, and for the establishment of mechanisms to track the achievement of these objectives. This includes:

- advocating for the IRCC to develop and implement a standardized mechanism to track the specific security indicator(s) that trigger referrals to the NSSD; this should allow for regular monitoring of their usage by IRCC missions and of the impact on the number of referrals made

- advocating for the development and implementation of a strategy to measure the ongoing effectiveness of the new thematic indicators in terms of their impact on the quality of referrals sent to the NSSD

- The VP of I&E should engage in systematic outreach and communication activities with CBSA regional hearings and investigations units to increase mutual understanding of the HQ and regional roles and responsibilities in the front-end security screening (FESS) process, with a view to minimizing duplication and enhancing collaboration. This could include:

- establishing a working group at the managerial level to regularly exchange information on new trends and events of concern within countries, regions and globally, as well as best practices, lessons learned and challenges in screening claimants and in preparing well-documented cases for IRB hearings

- establishing a mechanism giving NSSD analysts and regional officers access to relevant intelligence (such as via subscription databases), and systematically share intelligence obtained (such as emerging trends seen with claimants from a specific country, or information shared by local police services) to enhance each other’s work

- enhancing communication to raise awareness of the NSSD’s processes and procedures, including the procedures to follow when regions need to ask the NSSD for more time before a referral is closed and IRB is notified about the completed screening

- The VP of I&E should advocate to address a number of key interdepartmental issues through the fora referenced in the trilateral MoU, including:

- the roles and responsibilities in performance measurement across the continuum

- the need for interdepartmental training

- adopting a whole-of-government approach to setting service standards, taking into account of inter-dependencies in service delivery

- the development and implementation, by IRCC, of a monitoring mechanism to determine whether all applicants who should be referred for screening are being referred

- The VP of I&E should ensure that NSSD analysts have reliable and up-to-date information on country- and region-specific concerns and that all GeoDesks and teams apply policies, procedures and processes consistently. This includes:

- conducting an internal exercise to map current security screening practices in each GeoDesk and teams within GeoDesks, and assessing whether improvements have been made in implementing a harmonized approach to security screening across the NSSD

- introducing a standardized approach to collecting, storing and updating information on countries’ social, political, economic changes, and to communicating such changes to analysts across GeoDesks in a timely manner

- The VP of I&E, in collaboration with the VP of ISTB, should develop a plan to:

- assess program priorities and, accordingly, make adjustment to the Secure Tracking System (STS) and the future replacement system (Security Referral Request Service), to start collecting additional data to support performance measurement

- ensure that the Security Screening Automation (SSA) is fully operational with all its advanced functionalities, including the text-query reading capability before retiring STS; this is in view of mitigating major risks associated with the transition to the new system

Introduction

Evaluation approach: Purpose and scope

This report presents the results of the evaluation of the Immigration National Security Screening (INSS) Program (the Program or the Security Screening Program) and fulfills the requirements of the 2016 Treasury Board Policy on Results. The evaluation focused on the five-year period of fiscal years 2014 to 2015 to 2018 to 2019 and examined the achievement of expected outcomes and the efficiency of the Program. This section indicates areas that were in and out of scope of this evaluation.

In scope of the INSS Program evaluation

- Activities, outputs and results achieved during FYs 2014 to 2015 to 2018 to 2019, including how the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) is meeting service standards

- Achievement of outcomes related to the CBSA immigration national security screening program

- Assessment of process efficiency and utilization of resources

- Assessment of interconnections between CBSA and its partners (Immigration, Refugee and Citizenship Canada – IRCC – and Canadian Security Intelligence Service – CSIS) as well as their impact on CBSA’s ability to deliver expected program results and

- GBA+ analysis

Out of scope of the INSS Program evaluation

- Assessment of the INSS Program’s relevance and

- Independent assessment of the performance and efficiency of partners and decision-makers

The evaluation team consulted the INSS Program Logic Model (Appendix B) and developed evaluation questions that focused on the following:

- Program’s ability to adhere to service standards and to provide legally defensible recommendations to IRCC

- Program’s ability to prevent inadmissible foreign nationals from entering or remaining in Canada

- The impact the Program has on diverse groups of applicants throughout the security screening process

- Adequacy of CBSA policies, processes and resources to support the implementation of the INSS Program

- Effectiveness of the working relationship among program partners to achieve expected outcomes and

- Extent to which program processes are efficient and resources are used optimally

Evaluation approach: Methodology

The evaluation methodology comprised qualitative and quantitative research methods and data collection that spanned multiple sources. These included legislation and program-related documents; case management data; CBSA financial data; semi-structured interviews with 46 key program representatives from CBSA (HQ and Regions), IRCC, CSIS, and the Department of Justice Canada (JUS); and survey responses from 66 CBSA security screening analysts and 130 IRCC officers based in overseas missions. Details on the evaluation methods used are provided in Appendix C.

IRCC and CSIS supported this evaluation by identifying key stakeholders in their respective organizations for interviews. IRCC, in addition, supported the implementation of the survey conducted among IRCC officers, and provided case management data on the number of immigration applications over the five-year evaluation period and other data related to IRCC’s assessment and decisions issued on Temporary Resident (TR), Permanent Resident (PR), and Refugee Claimant (RC) applications.

Two main limitations were identified during the evaluation. First, the timelines for data collection were extended due to delays in obtaining the required case management data. Also, the data collection process was impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic, as the survey with IRCC officers had to be postponed for several months and the target population was reduced.

Program background: Immigration security screening—The Government of Canada approach

Foreign nationals seeking entry to Canada are screened against specific sections of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA) to identify potential security concerns. Security screening of foreign nationals is a joint collaboration between IRCC, CBSA and CSIS. TR and PR applications are processed by IRCC through a network of missions abroad, as well as processing centres located within Canada. IRCC assesses applicants’ personal information and history against a set of criteria – the security screening indicators – to determine whether applicants may pose a potential security risk. If IRCC officersFootnote 1 have inadmissibility concerns over a PR or TR application, they refer it for an in-depth security screening to the CBSA and, depending on the nature of the concern, also to CSIS. The CBSA and CSIS screen all adult RC applicants (see Front-end security screening of refugee claimants).

The CBSA screens applicants for potential inadmissibility concerns under section 34 (espionage, subversion, terrorism, danger to the security of Canada, membership in an organization that engages in the aforementioned acts, or violence), and/or section 35 (crimes against humanity, war crimes, genocide, sanctions) and/or section 37 (organized criminality). CSIS only screens applicants for concerns under the Canadian Security Intelligence Service Act, related to determining inadmissibility under section 34 of IRPA. Here, CSIS provides input to the CBSA, who then finalizes the screening with additional searches and information. Upon completing the screening of an application, the CBSA provides a recommendation and any CSIS security advice to IRCC in case of TR and PR applicants, and sends a notification on the recommendation issuance to the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (IRB) in case of in-Canada refugee claimantsFootnote 2. IRCC or IRB then makes a decision on the outcome of the application. The process for assessing refugee claimants is detailed in Front-end security screening of refugee claimants.

Immigration national security screeningFootnote 3: Canada Border Services Agency responsibilities

Security Screening is listed in the 2018 to 2019 CBSA Departmental Results Framework under the Border Management core responsibility. Applications requiring security screening are assessed by the CBSA’s National Security Screening Division (NSSD) within the Intelligence and Enforcement Branch. As of July 2015, the NSSD was organized around Geographic Desks (GeoDesks)Footnote 4, with analysts processing security screenings from countries within a designated region. If needed, analysts are assigned to process referrals from other GeoDesks.

NSSD is responsible for conducting security screening for all three business lines — temporary residents, permanent residents and refugee claimants. Referred cases are reviewed to determine if all the required information has been provided; afterwards, a security screening is conducted by an NSSD analyst. A screening results in one of the following outcomes:

- Favourable

- If no security concerns are found, NSSD issues a favourable recommendation

- Non-favourable

- If initial checks or research reveals security concerns, the case is referred to a senior analyst who reviews the information and conducts additional research. If the derogatory information meets IRPA’s threshold of reasonable grounds to believe, NSSD prepares a brief to accompany the non-favourable recommendation that will be issued

- Inconclusive

- In some cases, NSSD may close a referral with an inconclusive result, whereby the admissibility of an applicant could not be determined due to insufficient information or due to some other circumstances

- No recommendation required

- Occurring mostly in the RC business line, this outcome is entered if a referral was made in error, the applicant was under the age of twelve with no indication of inadmissibility, or otherwise if an assessment was no longer required

In addition, NSSD briefs known as “Favourable with Observations” and “Inconclusive with Observations” are also shared with decision-makers, where the reasonable grounds to believe threshold for inadmissibility was not met, but where it was deemed that information encountered during security screening could impact the final decision.

NSSD shares its admissibility recommendations with decision-makers (either IRCC or IRB), incorporating security advice from CSIS for all applicants screened for potential inadmissibility under section 34 of IRPA. For TR and PR applicants, NSSD sends the recommendations to the relevant IRCC office, where the NSSD’s assessment is considered in the decision to allow or deny the applicant’s stay or entry into Canada. In case of refugee claimants, the recommendation is transferred to CBSA Regional Offices for further processing (see Front-end security screening of refugee claimants), and the NSSD notifies the IRB on the recommendation issuance.

Front-end security screening of refugee claimants

Since Refugee Reform in 2012, all adult individuals who submit a refugee claim in Canada aged 18 years and older are subject to the Front-End Security Screening (FESS) process. Upon completion of the claim intake process, the intake officerFootnote 5 will refer the claim to the NSSD and CSIS, and to one of three refugee claim triage centres, for processing. Once the security screening has been completed, the NSSD sends a notification to the IRB. The Division also shares the screening result with the CBSA hearings unit and inland office in the region where the claim is being processed. In addition, the triage centres in each region assess all in-Canada refugee claimants independently from the NSSD to determine whether there are security concerns. If so, the case will be referred to the regional investigations unit and, if deemed meritorious, the hearings unit will be engaged to determine if an intervention is warranted at the IRB hearing.

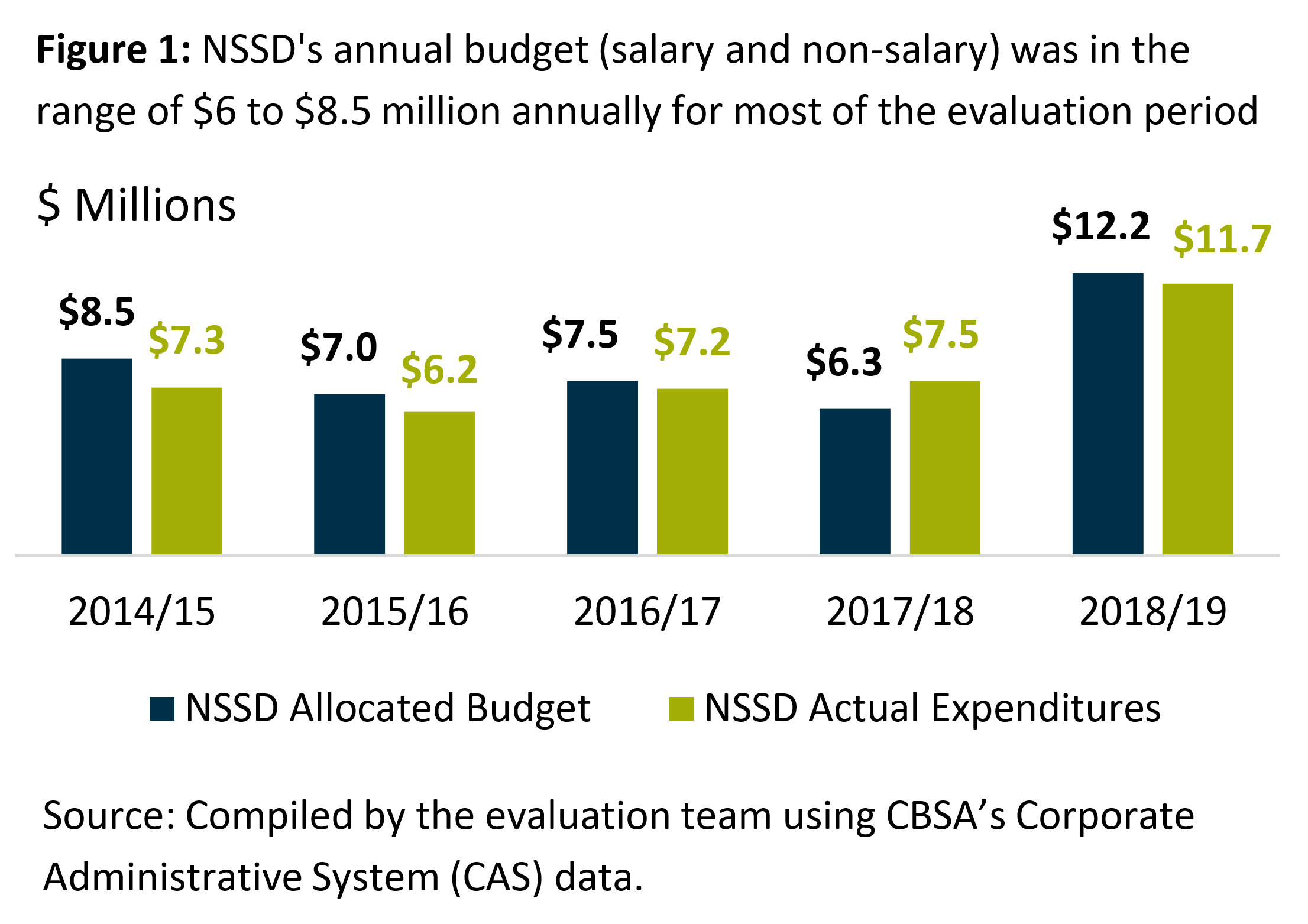

National Security Screening Division budget

The NSSD’s budget and expenditures were relatively stable for the first four years of the evaluation period, before increasing in the final year. From 2014 to 2015 to 2017 to 2018, the budget fluctuated within the $6 to $8.5 million range. The NSSD’s budget then almost doubled from 2017 to 2018 to 2018 to 2019 to respond to the increasing workload experienced in the preceding years. In terms of expenditures, the NSSD spent within its allocated budget in every year except for 2017 to 2018 (see Figure 1).

Text version: Figure 1

NSSD's annual budget

- 2014 to 2015: The NSSD allocated budget was $8.5 million. NSSD actual expenditures were $7.3 million

- 2015 to 2016: The NSSD allocated budget was $7 million. NSSD actual expenditures were $6.2 million

- 2016 to 2017: The NSSD allocated budget was $7.5 million. NSSD actual expenditures were $7.2 million

- 2017 to 2018: The NSSD allocated budget was $6.3 million. NSSD actual expenditures were $7.5 million

- 2018 to 2019: The NSSD allocated budget was $12.2 million. NSSD actual expenditures were $11.7 million

Source: Compiled by the evaluation team using CBSA’s Corporate Administrative System (CAS) data.

- Date modified: