Evaluation of the Immigration National Security Screening Program: Achievement of program objectives

NSSD seeks to provide timely and legally defensible recommendations to decision-makers. Over the five-year evaluation period, NSSD delivered legally defensible recommendations that contributed to preventing inadmissible individuals from entering or remaining in Canada. However, for most of the period, these recommendations were not provided within the service standards. The NSSD’s workload (i.e. the number of referrals it receives for screening every month) is determined by factors beyond its control, with two significant and unforeseen events—Operation Syrian Refugee (OSR) and increased irregular migration (IIM)—having had a major impact on the NSSD’s ability to issue timely recommendations.

Legal defensibility of recommendations

A key challenge with assessing legal defensibility is that it has not been specifically defined by the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) and/or partners, and there is no concrete agreement on what constitutes a legally defensible recommendation. Legal defensibility is also not regularly tracked or discussed with partners.

The evaluation focused on two specific areas relating to the legal defensibility of admissibility recommendations—the number of legal challenges to immigration decisions submitted by applicants and NSSD’s application of the law in its security screening assessments.

Applicants' legal challenges of immigration decisions

Finding 1: Only a small proportion of immigration decisions denied on security grounds were challenged by applicants, and only a few were successful from the applicant’s standpoint.

Under Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA), a foreign national can ask the Federal Court of Canada to review immigration decisions issued by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) or Immigration and Refugees Board (IRB). Although the CBSA’s role is to issue security screening recommendations and not to decide on the application, if the decision is being challenged because of security inadmissibility, the Agency’s Litigation Management Unit (LMU) may become involved alongside the Department of Justice Canada. However, the majority of cases are handled by IRCC’s legal team.

A total of 292 challenges by applicants to decisions based on security inadmissibility were registered between 2014 to 2015 and 2018 to 2019, which represents 4% of all the 7,673 non-favourable recommendations issued. The majority of these challenges (76%) were from overseas applicants, and handled by the IRCC litigation team. More than 80% of all the challenges were from permanent residence (PR) applicants, the majority of whom were denied their applications based on section 34 concerns.

Of the 292 challenges, 51% (148) were allowed to proceed to a Judicial Review. Of those cases:

- 30% (45) were decided in favour of the government

- 24% (36) were decided in favour of the applicant

- 35% (51) resulted in IRCC consenting to re-determine its original decision (the legal challenge was discontinued)

- 11% (16) were withdrawn or still ongoing at the time of the evaluation

Only 36 of the 292 challenges were decided in favour of the applicant, which represents less than 0.5% of all non-favourable recommendations issued by NSSD. Considering that NSSD processed close to half-a-million of referrals over the evaluation period, 36 successful legal challenges could be considered a low number. However, there is currently no established benchmark or performance indicator to determine what rate of legal challenges and/or applicant’s success rate is desirable.Footnote 6

It is also important to recognize that legal challenges most commonly resulted in the decision-maker (almost exclusively IRCC) consenting to re-determine the original decision without waiting for the Court’s decision either on the Leave stage or Judicial Review. When both phases of the legal challenge are considered, half (50%) of challenges were “settled” out-of-court (79 cases in the Leave phase and 33 during Judicial Review). The fact that the decision-maker agrees to re-determine a decision on an application does not mean that the decision will change; instead, the government entity in the decision-maker role acknowledges that there may have been some administrative or procedural faults and asks a different staff (IRCC officer or IRB member) to review the case and render a fresh decision.

Application of the law in security screening

Finding 2: NSSD’s admissibility recommendations were well grounded in legislation, although the usability of the information contained in inadmissibility briefs could be improved.

Views on legal defensibility of recommendations

NSSD managers generally considered the Division’s recommendations to be based on solid legal evidence and to be legally defensible. They cited some recent high-profile cases whereby the NSSD’s recommendation was challenged by partners in IRCC and/or another department supporting the applicant’s visit to Canada, but the initial screening recommendation was upheld. In addition, the generally low number of cases where IRCC disagrees with NSSD’s screening recommendation (i.e. contrary outcomesFootnote 7) was also seen as an indication of their legal defensibility.

However, the same stakeholders also admitted that it is difficult to assess what constitutes legally defensible recommendations and to develop associated performance measures. Both NSSD and LMU/the Department of Justice Canada (JUS) stakeholders agreed that Court decisions are unlikely to be a reliable measure, as even a well-founded case can be decided either way on a given day by a given judge. In addition, on rare occasions, NSSD may wish to proceed with Court review to obtain more clarity on a specific case, regardless of what the outcome of the legal challenge is going to be. Consequently, legal defensibility is better thought of as NSSD doing its due diligence and legal counsels finding the case solid and deciding to defend it in the Court, rather than the actual Court’s decision.

External stakeholders had a less favourable view of the legal defensibility of NSSD’s recommendations. This stems primarily from the low usability of the information included in NSSD briefs, which can jeopardize procedural fairness. NSSD briefs accompany a non-favourable recommendation and allow the IRCC officer or CBSA inland/hearings officer to get acquainted with the evidence substantiating the recommendation. However, the briefs are often based on classified information and, depending on the sensitivity level of the contents, the derogatory information may or may not be disclosed to the applicantFootnote 8. Even if a brief is not based on classified information, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) and/or the CBSA can still request that the complete brief not be shared with the applicant. If such a request is granted, not disclosing the reasons for an application refusal denies the applicant the possibility to fairly participate in the process, which is a core principle of procedural fairness. Procedural fairness requires that applicants be provided with a fair and unbiased assessment of their application, be informed of the decision-maker’s concerns and have a meaningful opportunity to provide a response to concerns about their applicationFootnote 9.

Access to legal advice

NSSD analysts had access to legal advice on a regular basis throughout the evaluation period through bi-weekly legal counselling sessions provided by LMU and/or JUS counsels. These sessions allowed analysts to discuss their current referrals, or recurring issues in their screening activities more generally. Some NSSD managers indicated that this regular access to legal advice helped to ensure recommendations were legally defensible. However, as participation in the legal counselling sessions is voluntary, legal knowledge/application among analysts may be uneven.

In terms of other support, JUS provided an updated document on relevant jurisprudence relating to IRPA to NSSD analysts on a semi-annual basis, which provided specific IRPA definitions, such as “reasonable grounds to believe,” “espionage” and “subversion.” For each of these terms, there were citations from past court decisions with additional links to other relevant court rulings.

Strengthening the legal defensibility of recommendations

There were several areas for which the legal defensibility of recommendations could be strengthened:

Classification of information and Procedural Fairness. NSSD sometimes has to base its inadmissibility recommendation solely on classified information received from CSIS or from its own research. In the absence of open-source or unclassified information, IRCC cannot disclose the reason for application refusal to the applicant, therefore denying the applicant procedural fairness. In some such cases, the IRCC officer may believe that visa issuance is required in order to meet procedural fairness.

[redacted]

Contribution to preventing inadmissible individuals from entering or remaining in Canada

By providing well-substantiated admissibility recommendations, NSSD seeks to provide all relevant information to support decisions on who is issued a visa and who is allowed to stay in Canada in favour of maintaining public safety. To assess this, the evaluation looked at the alignment between the NSSD’s recommendations and decisions on applications by IRCC.Footnote 10 The evaluation also examined the extent to which NSSD’s assessments correctly identified individuals who were, in fact, admissible. If NSSD conducted all checks and came up with a well-researched admissibility recommendation that was followed by IRCC, there should be a low probability of that person being later identified as having committed an activity related to their inadmissibility, and being detained, issued a removal order and/or effectively removed from Canada. The evaluation tested this hypothesis by comparing favourable security screening recommendations with CBSA data on enforcement actions based on sections 34, 35 and 37 of IRPA.Footnote 11

Extent to which recommendations are followed by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

In the case of temporary residence (TR) and PR applications, IRCC is the decision-maker, and officers use the result of NSSD’s screening to guide their decisionsFootnote 12. However, there may be other factors that affect a decision on an application, such as requests by other federal departments for applications to be approved in the national interest for high-profile foreign nationals who are inadmissible under IRPA. In such instances, the decision on the application may not correspond to the NSSD admissibility recommendation.

Finding 3: Due to multiple factors and considerations, IRCC authorized entry or permission to stay in Canada to a significant proportion of applicants who had received a non-favourable recommendation or an inconclusive screening result from NSSD.

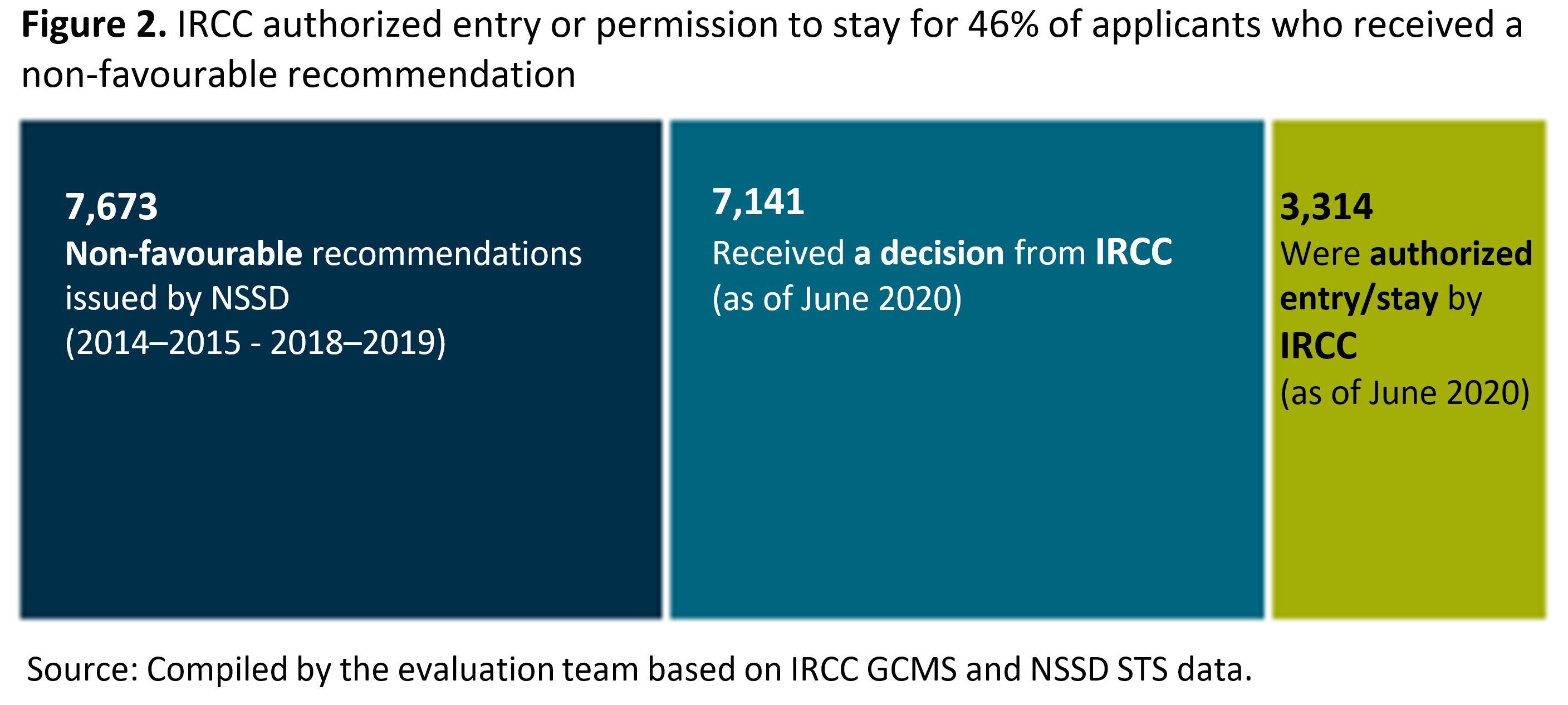

As can be seen from Figure 2, between 2014 to 2015 and 2018 to 2019, the NSSD issued 7,673 non-favourable recommendations; of those applicants who received a decision, IRCC authorized entry to or permanence in Canada in a little under half of cases (46%).

Text version: Figure 2

Between fiscal years 2014 to 2015 and 2018 to 2019, 7,673 non-favourable recommendations were issued by NSSD.

As of June 2020, 7,141 applicants had received a decision from IRCC.

As of June 2020, 3,314 applicants were authorized entry/stay by IRCC.

Source: Compiled by the evaluation team based on IRCC GCMS and NSSD Secure Tracking System (STS) data.

The two most common scenarios under which IRCC authorizes entry for applicants who received a non-favourable recommendation are as follows:

- Public policy exemption (PPE)

- An applicant who is deemed inadmissible may receive a public policy exemption that is based on a National Interest Letter from a federal entity (usually other than IRCC), which deems that the entry of this person to Canada is in the country’s national interest

- Contrary outcome

- An instance where IRCC disagrees with NSSD’s assessment of an applicant’s inadmissibility and decides to approve the application

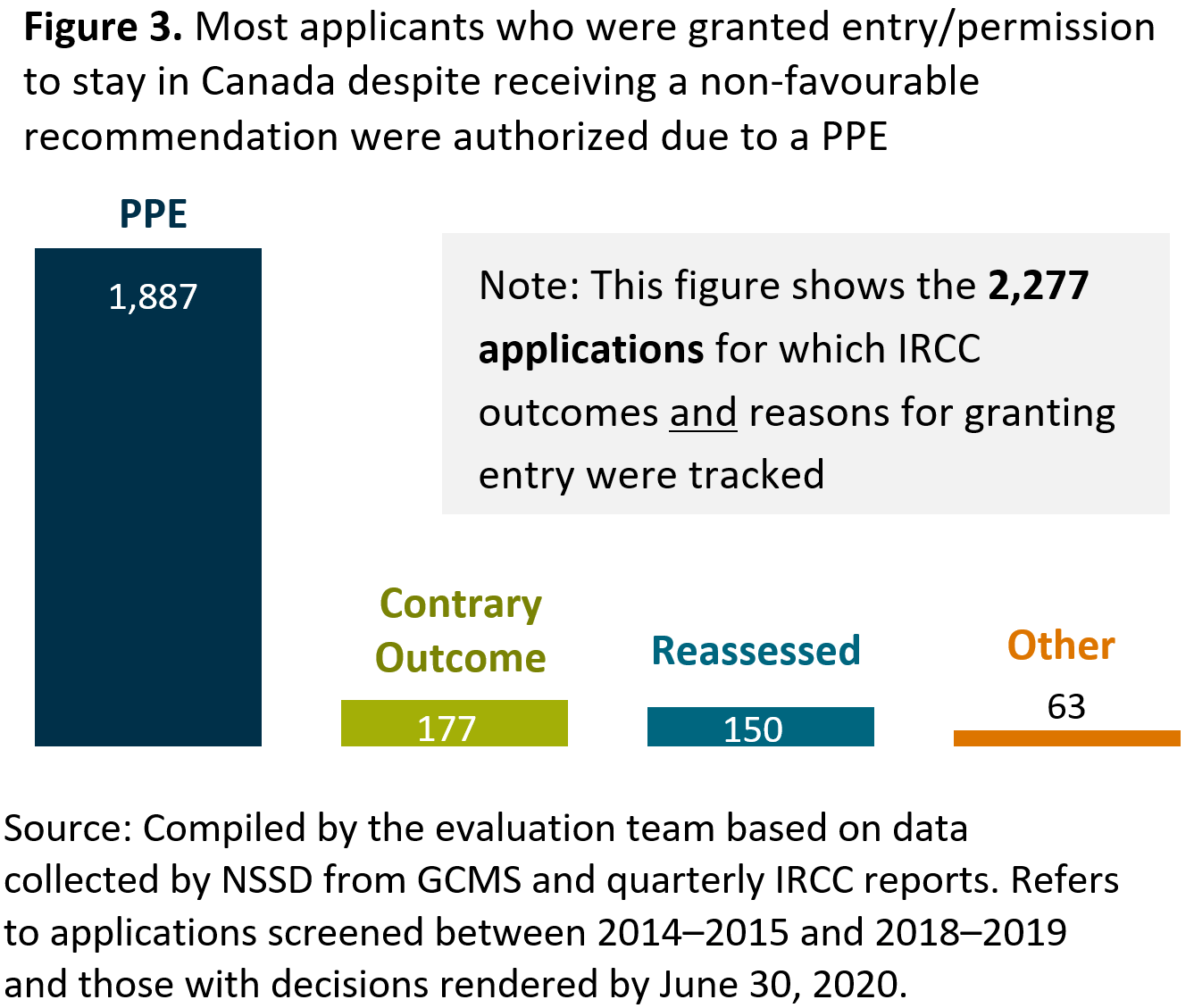

According to data compiled by NSSD, the vast majority of inadmissible individuals were authorized entry to Canada by IRCC due to national interest reasons (PPE). Of the applicants who received a non-favourable recommendation from NSSD and were issued a visa, four out of every five were granted entry due to a PPE (see Figure 3).

Text version: Figure 3

This figure shows the 2,277 applications for which IRCC outcomes and reasons for granting entry were tracked:

- PPE = 1,887 applicants

- Contrary outcome = 177 applicants

- Reassessed = 150 applicants

- Other = 63 applicants

Source: Compiled by the evaluation team based on data collected by NSSD from GCMS and quarterly IRCC reports. Refers to applications screened between 2014 to 2015 and 2018 to 2019 and those with decisions rendered by June 30, 2020.

NSSD may also issue an inconclusive finding result on an application. While there are various scenarios under which this could occur (e.g. missing information, application withdrawn, applicant referred in error)Footnote 13, interviewees indicated that the most common reason is because NSSD [redacted]. Of the 14,290 referrals closed as inconclusive between 2014 to 2015 and 2018 to 2019, the vast majority (81%) were granted entry by IRCC; only 10% were refused. The remaining applications were withdrawn or were pending decision.

In cases where applications were incomplete, the missing information often could not be requested by IRCC officers due to bilateral irritants. Given that NSSD only issues inconclusive results when concerns may exist and cannot be ruled out, NSSD managers and some analysts note that inconclusive screenings should indicate a warning to IRCC rather than a “green light” to proceed with the application. On the other hand, without specific information indicating inadmissibility, the IRCC officers generally do not have sufficient grounds on which to deny the applicationFootnote 14.

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada officers' views on the quality of recommendations and their actions in case of disagreements

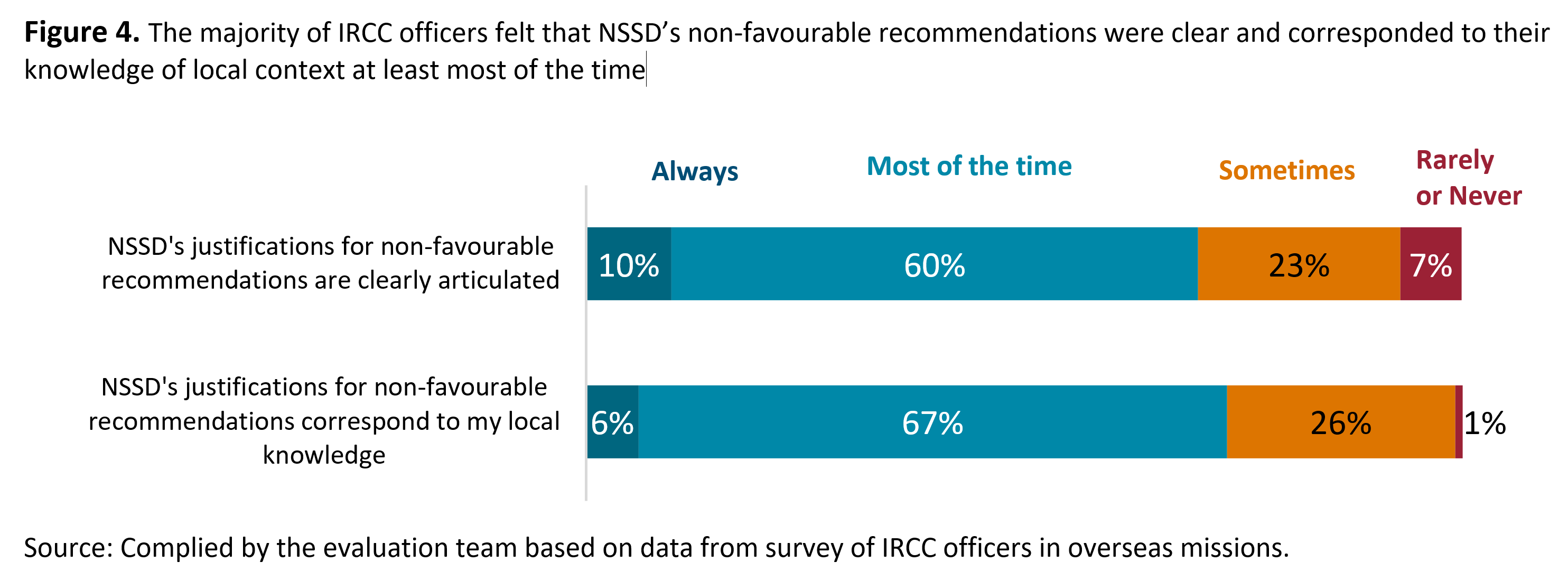

Overall, mission-based IRCC officers who responded to the evaluation survey were satisfied with the quality of recommendations issued by NSSD. 70% of officers felt the NSSD’s reasons for issuing non-favourable recommendations were clearly articulated always or most of the time; nonetheless, a sizeable proportion (30%) only “sometimes” or “rarely or never” found this to be the case. Almost three quarters (73%) of IRCC officers thought that the NSSD’s justifications for issuing non-favourable recommendations were always or most of the time in line with their own knowledge of the local context; however, almost three in ten did not (see Figure 4).

Text version: Figure 4

- When asked if NSSD’s justifications for non-favourable recommendations are clearly articulated:

- 10% of overseas IRCC officers responded always

- 60% of overseas IRCC officers responded most of the time

- 23% of overseas IRCC officers responded sometimes

- 7% of overseas IRCC officers responded rarely or never

- When asked if NSSD’s justifications for non-favourable recommendations corresponds to my their local knowledge:

- 6% of overseas IRCC officers responded always

- 67% of overseas IRCC officers responded most of the time

- 26% of overseas IRCC officers responded sometimes

- 1% of overseas IRCC officers responded rarely or never

Source: Compiled by the evaluation team based on data from survey of IRCC officers in overseas missions.

The vast majority of overseas IRCC officers (89%) had disagreed at some point with a non-favourable screening result issued by NSSD. According to the Immigration Control (IC) Manual, before making a decision contrary to NSSD’s recommendation, the IRCC officer should engage in a consultation process with NSSD which, in turn, engages CSIS. The responses of almost half (46%) of IRCC officers were in line with the official guidance, whereas just under one-quarter (23%) indicated that they would request guidance from IRCC headquarters as a next step.

Enforcement actions against approved applicants with non-favourable recommendation

If a foreign national with TR or PR status in Canada is found to have engaged in activities of concern related to IRPA sections 34, 35 or 37, they may become subject to an enforcement action by the CBSA. To quantifyFootnote 15 if, and to what extent, individuals with a non-favourable recommendation or inconclusive screening result were later determined to be inadmissible, the evaluation looked into enforcement actions associated with these individuals. The analysis of data revealed that most applicants admitted or allowed to stay in Canada despite a non-favourable or inconclusive screening result had no enforcement actions taken against them:

-

Applicants screened as non-favourable and received a PPE

No applicants who entered Canada under PPE permits were subsequently subject to any of the above-mentioned enforcement actions

-

Applicants screened as non-favourable, but IRCC disagreed (“contrary outcomes”)

No applicants whose visas were issued based on a contrary outcome were subsequently subject to any of the above-mentioned enforcement actions

-

Applicants screened as inconclusive, but approved

[redacted] applicants with an inconclusive security screening result and who were authorized by IRCC were in the removal inventory as of August 2020. This represents [redacted] of all application with inconclusive screening results that were approved. [redacted] of the applicants faced allegations under paragraph 35(1)(a) – crime against humanity – and two under paragraph 34(1)(f) – membership in a terrorist organization. The immigration decisions for these applicants were issued in 2017 and 2018, but it took until 2020 for the inadmissibility exam reports for all [redacted] of them to be finalized. All [redacted] were in the Monitoring Inventory (i.e. not readily removable) at the time the data was collected

While the data shows that foreign nationals screened as non-favourable who were authorized to enter or stay in Canada did not face any enforcement actions, it should be noted that not all risk is captured through enforcement actions, nor can it be fully monitored through surveillance. As a few interviewees pointed out, having these individuals in Canada could have negative consequences for the country’s reputation or result in actions that are more difficult to intercept and act on (e.g. business espionage or threatening Canadian residents), particularly as most of these individuals are short-term visitors. Some stakeholders also noted that not following admissibility recommendations issued by security partners has had a significant negative impact on the morale of NSSD’s analysts and undermines the integrity of the security screening process.

While the proportion of applicants screened as inconclusive with an enforcement action against them was low, there are associated risks to the security of Canada, as well as to program integrity. One individual with an inconclusive screening result was authorized entry to Canada but was later alleged to be a member of a terrorist organization and ended up in the Removal inventory; as such, the risk to public safety of this individual being in Canada was potentially very high. However, NSSD is not the decision-maker on applications, so the enforcement actions against these applicants do not reflect the Division’s effectiveness in terms of the screenings it performed.

Enforcement actions against applicants or claimants who were screened favourably

Finding 4: A negligible proportion of applicants who were screened favourably by NSSD were subsequently subject to an enforcement action.

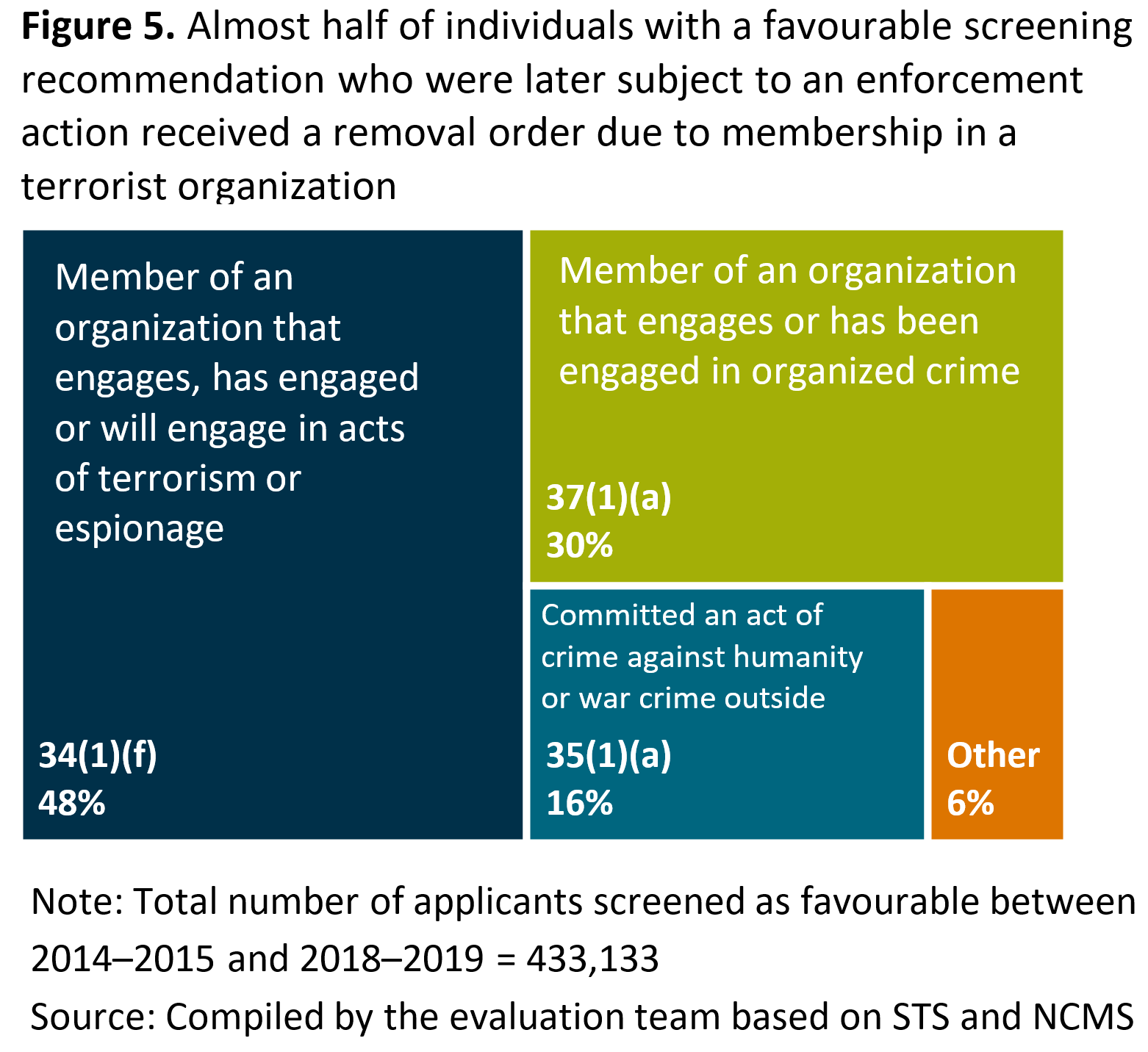

A total of 295 applicants who received a favourable screening recommendation from NSSD and were admitted to, or allowed to remain in Canada were subsequently subject to an enforcement action. This represents 0.07% of all those who received a favourable recommendation during the evaluation period.

Most (83%) were in the removal inventory at the time of the evaluation, while a few (11%) had been removed from Canada. Additionally, of the 295 individuals, the [redacted] refugee claimants (83%), close to one quarter (24%) were [redacted], and almost half (48%) were alleged members of an organization that engages in acts of terrorism (see Figure 5).

Text version: Figure 5

Figure 5 shows that almost half of individuals with a favourable screening recommendation who were later subject to an enforcement action received a removal order due to membership in a terrorist organization:

- 48% were a member of an organization that engages, has engaged or will engage in acts of terrorism or espionage

- 30% were a member of an organization that engages or has been engaged in organized crime

- 16% committed an act of crime against humanity or war crime outside of Canada

- 6% other

Note: Total number of applicants screened as favourable between 2014 to 2015 and 2018 to 2019 = 433,133

Source: Compiled by the evaluate on team based on STS and NCMS data

It should be noted that an enforcement action on an individual who was screened favourably by NSSD could be due to factors that were not present or known at the time NSSD completed their screening. The Agency currently does not collect data that separates such instances from those where NSSD did not conduct its screening thoroughly.

Timeliness of NSSD's recommendations

In addition to legal defensibility, the NSSD aims to issue timely recommendations that adhere to established service standards. Each business line has its own service standards, which specify the number of days it should take NSSD to process a referral, and each GeoDesk receives a unique case mixFootnote 16. NSSD’s performance target is to process 80% of all referrals in each category within the established service standard in any given monthFootnote 17Footnote 18.

TR and PR service standards are jointly-agreed upon between IRCC, NSSD, and CSIS. For RC service standards, the timeline for processing referrals is adjusted based on the legislated timeline within which the IRB is required to schedule a hearingFootnote 19. Service standards also vary depending on the urgency or purpose of the applicationFootnote 20, and on the IRCC mission where the application was submitted. The evaluation used the service standards that were in effect from 2014 to 2015 to 2018 to 2019 (see Appendix D).

Relevance of and ability to meet current service standards

Finding 5: While service standards support the timely delivery of admissibility recommendations and set expectations as to the length of the screening process, NSSD did not meet its related performance target for most of the evaluation period.

Without doubt, the service standards used by NSSD support the delivery of the INSS Program by providing decision-makers with an expected timeframe for receiving admissibility recommendations. Both NSSD management and Program partners who were consulted agreed that NSSD’s service standards were helpful. This is because they allow NSSD to prioritize its workload based on the urgency and priority of referralsFootnote 21; support Program partners in setting timelines for their own processes that happen concurrently or in dependence on NSSD’s security screening; and function as a measure of overall Program performance. While the service standards are considered helpful, the evidence in recent years indicates that they were not consistently met.

- Operation Syrian Refugee (OSR)

- Through OSR, Canada resettled 26,172 Syrian refugees from December 2015 to February 2016 (Audit of OSR, 2017). OSR resulted in the addition of a large number of referrals to NSSD’s workload. OSR refugees were pre-assessed at missions abroad and applied to come to Canada as permanent residents rather than refugee claimants.

- Increased Irregular Migration (IIM)

- Between July 2017 and March 2020, 55,677 irregular migrants crossed the Canada–U.S. border and claimed refugee protection status in Canada. As per the FESS policy, all adult claimants were referred to NSSD for security screening. (Source: IRB)

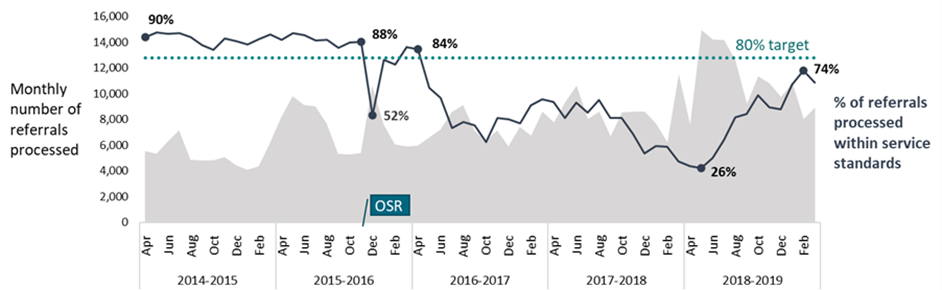

Between 2014 to 2015 and 2018 to 2019, NSSD mostly did not meet its 80% performance target (see Figure 6). The major cause of this trend was Operation Syrian Refugee (OSR) in 2015 to 2016, while increased irregular migration (IIM) at the Canada–U.S. border beginning in 2017 to 2018 caused a new surge in referrals that further hindered NSSD’s ability to meet its performance target. It was not until mid-2018, and after the adoption of a comprehensive suite of backlog reduction measures (see Backlog reduction and transformation action plan), that the NSSD moved closer to achieving its target again.

Text version: Figure 6

Figure 6 shows that the NSSD mostly did not meet the service standards performance target after OSR

| Year | Monthly number of referrals processed | % of referrals processed within service standards | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 to 2015 | Apr | 5,543 | 90% |

| May | 5,317 | 92% | |

| Jun | 6,277 | 92% | |

| Jul | 7,132 | 92% | |

| Aug | 4,896 | 90% | |

| Sep | 4,838 | 86% | |

| Oct | 4,838 | 84% | |

| Nov | 5,106 | 89% | |

| Dec | 4,474 | 88% | |

| Jan | 4,085 | 86% | |

| Feb | 4,354 | 89% | |

| Mar | 6,186 | 91% | |

| 2015 to 2016 | Apr | 8,191 | 89% |

| May | 9,826 | 92% | |

| Jun | 9,107 | 91% | |

| Jul | 9,048 | 88% | |

| Aug | 7,670 | 89% | |

| Sep | 5,339 | 85% | |

| Oct | 5,269 | 87% | |

| Nov | 5,405 | 88% | |

| Dec | 10,652 | 52% | |

| Jan | 7,603 | 79% | |

| Feb | 6,091 | 77% | |

| Mar | 5,894 | 85% | |

| 2016 to 2017 | Apr | 5,971 | 84% |

| May | 6,610 | 65% | |

| Jun | 7,206 | 61% | |

| Jul | 8,560 | 46% | |

| Aug | 9,133 | 49% | |

| Sep | 7,135 | 47% | |

| Oct | 6,323 | 39% | |

| Nov | 7,170 | 51% | |

| Dec | 5,934 | 50% | |

| Jan | 7,441 | 48% | |

| Feb | 6,745 | 57% | |

| Mar | 8,592 | 60% | |

| 2017 to 2018 | Apr | 7,767 | 59% |

| May | 9,340 | 51% | |

| Jun | 10,647 | 58% | |

| Jul | 8,052 | 53% | |

| Aug | 8,595 | 60% | |

| Sep | 6,664 | 51% | |

| Oct | 8,551 | 51% | |

| Nov | 8,611 | 43% | |

| Dec | 8,601 | 34% | |

| Jan | 7,656 | 37% | |

| Feb | 6,229 | 37% | |

| Mar | 11,540 | 30% | |

| 2018 to 2019 | Apr | 7,624 | 27% |

| May | 14,967 | 26% | |

| Jun | 14,190 | 31% | |

| Jul | 14,155 | 40% | |

| Aug | 12,553 | 51% | |

| Sep | 9,228 | 53% | |

| Oct | 11,357 | 62% | |

| Nov | 10,800 | 56% | |

| Dec | 9,772 | 55% | |

| Jan | 10,826 | 67% | |

| Feb | 8,047 | 74% | |

| Mar | 8,918 | 68% | |

Source: Compiled by the evaluation team based on the CBSA’s STS case management data.

The feasibility of achieving the service standards was questioned by NSSD analysts. According to the survey, only 9% of analysts felt the current service standards could be met in all circumstances; half (51%) of analysts considered them feasible only for referral received with all the required information, while an additional 38% felt they were feasible only for simple, complete referrals.

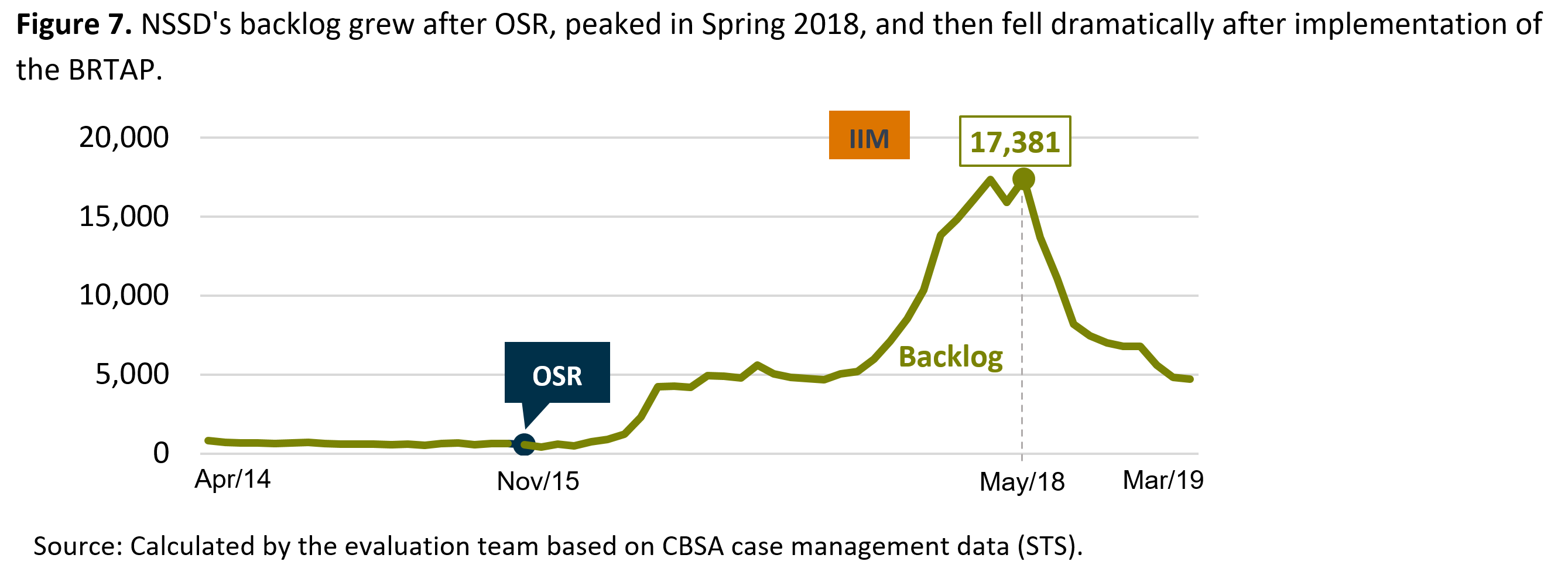

Operation Syrian Refugee and IIM as key factors in meeting the NSSD's performance target

OSR led to a steep increase in PR referrals for which NSSD was not sufficiently resourced to process. Between November 2015 and February 2016, NSSD processed 10,605 PR referrals as part of OSR, which represented 56% of all PR referrals processed during that period. The surge in referrals from OSR led to a sustained backlog growth, which was exacerbated by additional unanticipated referrals, particularly from IIM. By May 2018, the majority of screenings (61%), all business lines combined, had not been processed within their service standard. After implementing the Backlog Reduction and Transformation Action Plan, the backlog fell significantly; by March 2019, it had decreased by 73% (see Figure 7).

Text version: Figure 7

Figure 7 shows that the NSSD's backlog grew after OSR, peaked in Spring 2018, and then fell dramatically after implementation of the BRTAP. In May 2018, the backlog was at 17,381 referrals

- April 2014: 807

- November 2015 (OSR): 551

- May 2018: 17,381

- March 2019: 4,700

Source: Calculated by the evaluation team based on CBSA case management data (STS).

Rising referrals due to increased immigration

In addition to OSR and IIM, applications in other immigration streams gradually increased throughout the evaluation period. Between 2014 to 2015 and 2018 to 2019, the number of PR and TR applications submitted to IRCC grew by 70%. At the same time, the number of PR and TR referrals to NSSD grew by 84% (see Table 1). These trends are projected to continue, as Canada prepares to accept increasing numbers of immigrants in the years to come.Footnote 22

| Fiscal Year | TR and PR Applications | TR and PR Applications Referred for Security Screening | R and PR Referrals as a % of all PR and TR Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 to 2015 | 2,442,855 | 63,567 | 2.6% |

| 2015 to 2016 | 2,729,742 | 94,551 | 3.5% |

| 2016 to 2017 | 3,072,181 | 96,487 | 3.1% |

| 2017 to 2018 | 3,552,102 | 117,451 | 3.3% |

| 2018 to 2019 | 4,170,904 | 117,189 | 2.8% |

| Total | 15,967,784 | 489,245 | 3.1% |

| Source: Compiled by the evaluation team based on IRCC and CBSA case management data. | |||

NSSD's strategies to manage its workload

NSSD's initial response to Operation Syrian Refugee and IIM

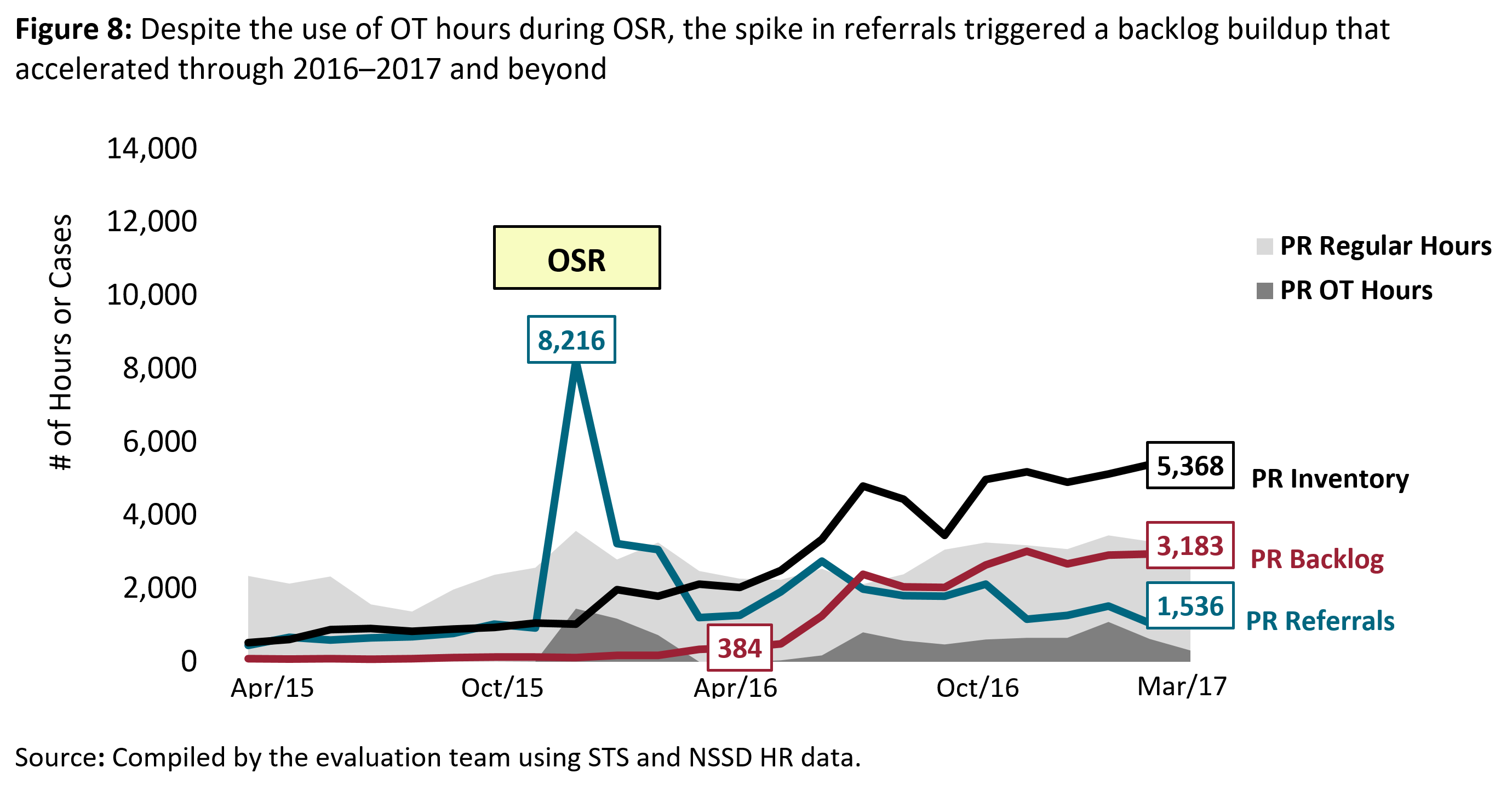

Finding 6: NSSD reallocated human resources and relied heavily on overtime (OT) to increase processing capacity when referrals grew, but these measures alone were not sufficient to overcome the backlog.

Inventory consists of all referrals received by NSSD that have not been completed (i.e. all “active” cases waiting to be processed)

Backlog consists of all referrals received by NSSD that have not been completed and are past their service standard

In response to OSR, NSSD increased staff hours dedicated to PR referrals, which included a substantial amount of OT. While OT had almost never been used from the start of the evaluation period up until then, an average of 840 OT hours were logged per month during OSR. Nonetheless, a steady rise in PR inventory and backlog continued from April 2016 onward (see Figure 8).

Text version: Figure 8

Figure 8 shows that despite the use of OT hours during OSR, the spike in referrals triggered a backlog buildup that accelerated through 2016 to 2017 and beyond

| Year | Number of cases for PR inventory | Number of cases for PR backlog | Number of cases for PR referrals |

|---|---|---|---|

| April 2015 | 523 | 86 | 448 |

| October 2015 | 936 | 132 | 1,022 |

| April 2016 | 2,022 | 384 | 1,269 |

| October 2016 | 4,977 | 2,640 | 2,109 |

| March 2017 | 5,368 | 3,183 | 1,536 |

Source: Compiled by the evaluation team using STS and NSSD HR data.

Even as PR backlog continued to increase significantly after 2015 to 2016, NSSD’s PR salary expenditures between 2016 to 2017 and 2017 to 2018 decreased due to the sudden increase of refugee screening referrals resulting from IIM. Essentially, NSSD did a further reallocation of staff to the RC business line, where the need was even more pressing.

Appendix I contains additional data on NSSD’s response in terms of salary expenditures and overtime hours.

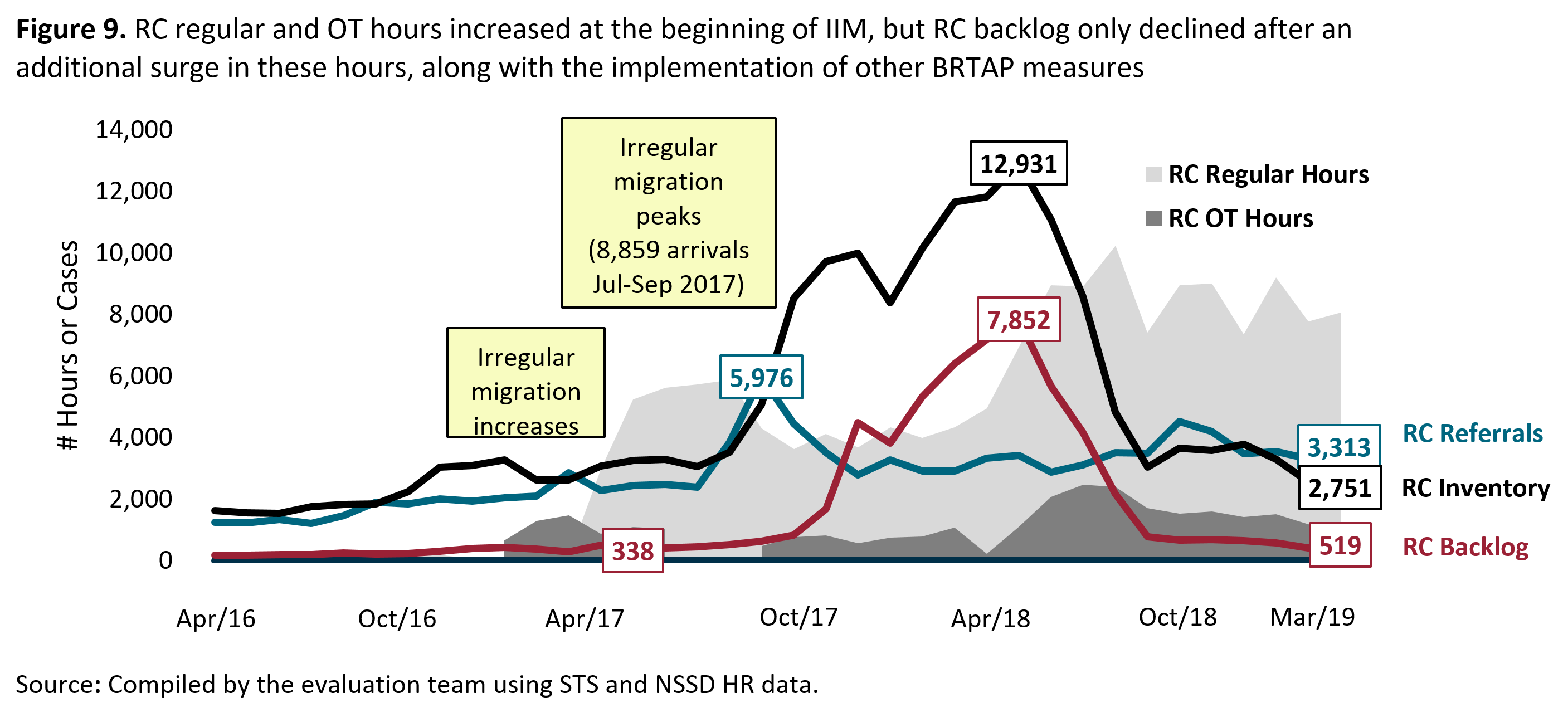

In fact, in response to IIM, NSSD significantly increased both regular and OT hours in the RC business line. In the 12 months after irregular migration first spiked in mid-2017, an average of 5,183 RC hours were logged per month, a 1,027% increase from twelve months prior. Despite this substantial increase, NSSD’s RC backlog climbed from a few hundred cases before IIM to close to 8,000 in April 2018—an increase of over 2,000%. After the BRTAP was enacted, the RC backlog fell sharply (see Figure 9).

Text version: Figure 9

Figure 9 shows that RC regular and OT hours increased at the beginning of IIM, but RC backlog only declined after an additional surge in these hours, along with the implementation of other BRTAP measures

| Year | Number of cases for PR inventory | Number of cases for PR backlog | Number of cases for PR referrals |

|---|---|---|---|

| April 2016 | 1,636 | 183 | 1,246 |

| October 2016 | 2,253 | 230 | 1,848 |

| April 2017 | 3,080 | 504 | 2,290 |

| October 2017 | 8,539 | 830 | 4,451 |

| April 2018 | 11,831 | 7,184 | 3,342 |

| October 2018 | 3,659 | 668 | 4,533 |

| March 2019 | 2,751 | 519 | 3,313 |

Source: Compiled by the evaluation team using STS and NSSD HR data.

In terms of salary and allocation of staff hours, NSSD responded to IIM proportionally to the increased workload resulting from the event. In 2017 to 2018, the proportional growth in RC salary expenditures almost exactly matched the proportional growth in the RC backlog; further salary expenditure increases followed in 2018 to 2019. NSSD’s response to IIM was driven by multiple pressures, including an inter-dependency with the IRB and the attention media accorded to the phenomenon.Footnote 23Footnote 24

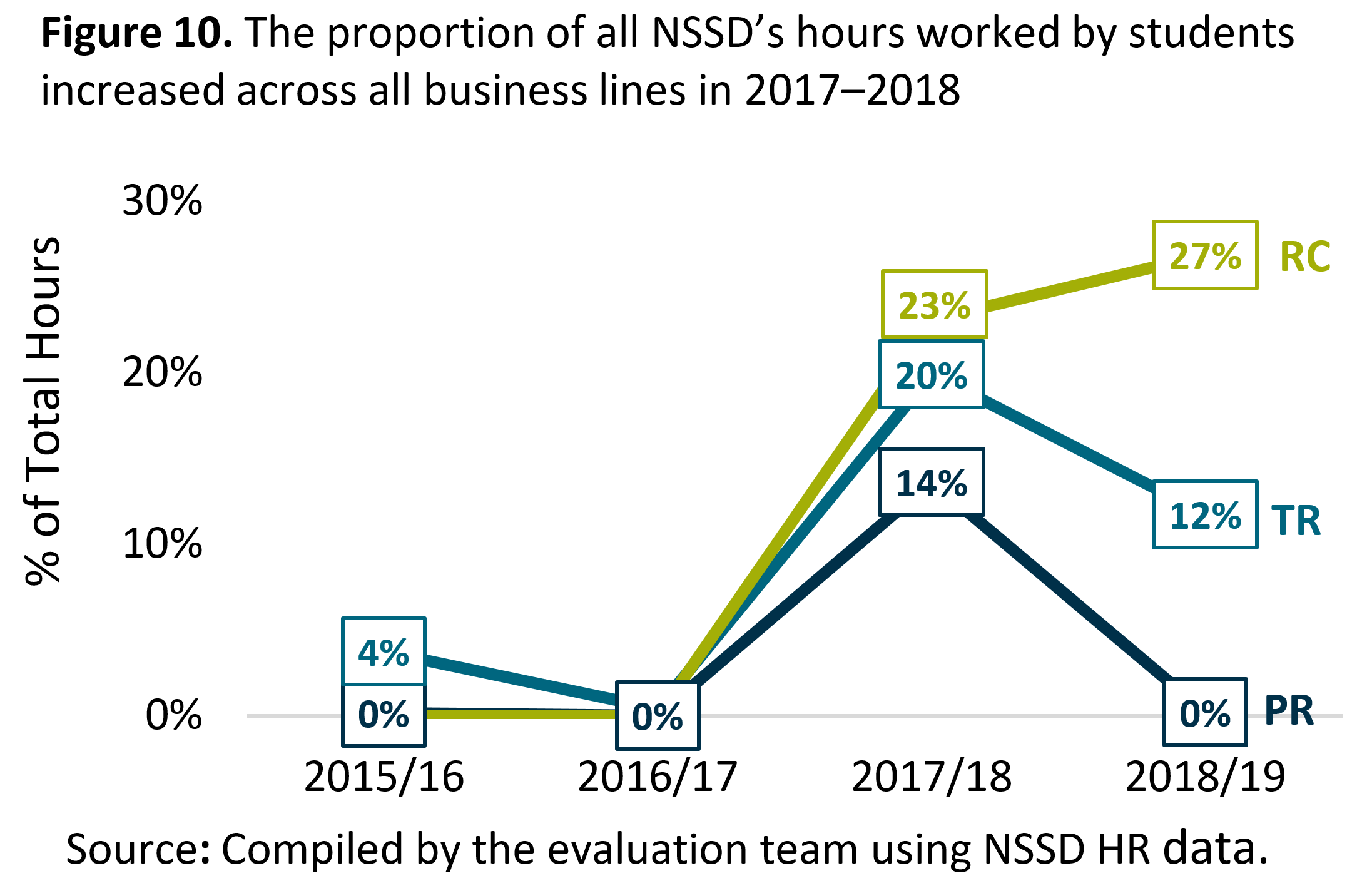

A notable difference in the response to IIM compared to OSR was the recruitment of a significant number of students starting in 2017 to 2018. As can be seen from Figure 10, students worked mostly on RC referrals (helping to reduce IIM backlog) and TR referrals. On the contrary, with the exception of 2017 to 2018, no students worked on PR referrals, despite a residual backlog from OSR. In addition to increasing processing capacity, student hires were also less costly compared to regular staff.

Text version: Figure 10

Figure 10 shows that the proportion of all NSSD’s hours worked by students increased across all business lines in 2017 to 2018.

| Year | % of total hours worked (refugee claimant) | % of total hours worked (temporary resident) | % of total hours worked (permanent resident) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015/16 | 0% | 4% | 0% |

| 2016/17 | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| 2017/18 | 23% | 20% | 14% |

| 2018/19 | 27% | 12% | 0% |

Source: Compiled by the evaluation team using NSSD HR data.

Backlog reduction and transformation action plan

Finding 7: Measures enacted through the Backlog Reduction and Transformation Action Plan (BRTAP) were effective in reducing the severe backlog.

The BRTAP was enacted in May 2018 in response to the unrelenting growth of NSSD’s backlog. Of the 64 BRTAP measures, 80% were implemented as of April 2020. These measures, listed in Appendix G, included internal operational and procedural changes, recruitment actions, and collaboration with partners to manage referrals and increase screening quality. In particular, the NSSD started collaborating with IRCC to manage the number of referrals it was receiving (e.g. via training IRCC officers and embedding an NSSD analyst within the Case Processing Centre in Ottawa) and to eliminate some of the unnecessary low-risk referrals being receivedFootnote 25.

NSSD regularly conducted analyses of the impact of the BRTAP measures through its Backlog and Referral Analyses and other pilot studies (see Performance measurement and Appendix F). Overall, these measures were effective in helping to reduce the backlog and in gradually improving the Division’s ability to meet its performance target related to service standards. By the end of the evaluation period, the NSSD had significantly reduced its backlog. NSSD stakeholders reported that this trend continued, and that the backlog was eliminated by April 2020.

Surge capacity

Finding 8: While a Surge Capacity Plan exists, the NSSD remains vulnerable to future sudden increases in referrals.

The NSSD developed a Surge Capacity Plan to manage future surges in referral numbers, which was one of the measures included in the BRTAP. The plan is built around five basic steps, including the targeted use of overtime by NSSD and other agency staffFootnote 26 and hiring students. However, additional measures could strengthen the plan, such as identifying and training a ready-to-deploy pool of employees across the Agency who could support the division at a short notice, and jointly considering possible courses of action with CSISFootnote 27.

Even without future referral surges, the base number of referrals is projected to increase in line with higher immigration targets. This will be challenging for the NSSD to manage both from a human and material (e.g. workstations) resource perspective; a fundamental adjustment to its current business model is likely required. To this end, NSSD is pursuing the Security Screening Automation (SSA) initiative, which should help the Division better manage its workload in the future; in the interim, NSSD is also pursuing implementation of Robotic Process Automation measures (see Security screening automation initiative).

Performance measurement

Finding 9: NSSD’s performance measurement is relatively limited; key variables have yet to be defined and outcomes are not yet fully articulated.

Performance measurement is key in defining the program’s objectives and strategies to measure their achievement. NSSD’s performance measurement largely focused on monitoring the Division’s inventory and its ability to reduce a backlog of cases. Considering that the backlog and overall referral numbers were on the rise for most of the evaluation period, monitoring the Division’s immediate processing capacity seemed like an obvious and inevitable performance measurement task. However, significant emphasis on the Program’s activities and outputs may have come at the expense of longer-term objectives.

Despite the existence of multiple levels of outcomes in the Program’s logic model (see Appendix B), the current key performance indicators (KPIs) only cover the timeliness aspect of the NSSD’s recommendations, measuring the intermediate outcome. The three KPIs are the proportions of recommendations completed within service standards as a percentage of all cases in the inventory in each month, for TR, PR, and RC cases, respectively. Each KPI has an associated target of 80%.

NSSD has adopted a largely quantitative approach to its performance monitoring, measuring the numbers of referrals processed on a weekly, monthly and quarterly basis. Specifically, NSSD produces statistical reports (capturing the current inventory, the ability to meet the KPIs, and number of recommendations issued by type) and backlog and referral reports (focusing on backlog reduction efforts, fluctuations to inventory, the rate of the different types of recommendations issued, and changes in referral numbers from certain offices).

While this data is important for the day-to-day management of the Program, there are key areas in performance measurement that have yet to be addressed. Specifically, there is no definition of a legally defensible recommendation and corresponding indicator(s) to capture this aspect of NSSD’s work (see Legal defensibility of recommendations). Defining the outcome and formulating corresponding indicators would help in measuring the logic model’s immediate outcome. There is also no systematic way of collecting feedback from decision-makers to determine if they consider NSSD’s recommendations to be either timely or legally defensible. NSSD maintains an informal system for tracking whether their recommendations were followed by IRCC but there is no similar system in place to monitor the decisions made on inland cases (refugee claims).

The evaluation team identified additional areas for which data is not currently being collected, including the number of “Favourable with Observations” and “Inconclusive with Observations” recommendations issued, the number of incomplete referrals received, and the percentage of inconclusive findings attributed to incomplete referrals.

- Date modified: