Evaluation of the Immigration National Security Screening Program: Factors impacting the achievement of objectives

A number of factors had an impact on the extent to which the National Security Screening Division (NSSD) was effective in its role, such as internal policies and procedures and training provided to NSSD analysts. In addition screening partners’ own workloads and processes impacted both the quantity and quality of referrals made, and in turn the NSSD’s ability to meet its performance target for service standards. NSSD and its partners took steps to increase the program’s effectiveness over the evaluation period.

Internal policies and training

Policies and procedures

Finding 10: NSSD’s policies and procedures have been enhanced, but opportunities exist to better equip analysts, such as by ensuring they are kept fully up-to-date on events of concern around the world.

Over the evaluation period, NSSD made significant efforts to introduce new policies and procedures and to update existing guidance, which was in response to the challenges NSSD faced in managing its workload. Additionally, there was collaboration via the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS)-led Fusion Centre initiative to ensure that the information CSIS provides is useful to, and useable by, NSSD analysts.

NSSD analysts generally viewed the internal policies and procedures positively. Most survey respondents considered the Division’s current policies and procedures to be readily accessible (91% of analysts), clear and concise (86%), and up-to-date (77%).

Despite the progress made in updating and introducing new policies and procedures, a number of gaps remain. Close to two-thirds (62%) of NSSD analysts agreed that internal security screening policies and procedures needed to be improved. 37% identified internal policies and procedures such as NSSD’s standard operating procedures (SOPs), front-end security process (FESS) and duplication with regions or making reading Basis of Claim mandatory as a key area requiring improvement. In addition, only half of surveyed analysts felt there was a process in place to continuously monitor and communicate events of concernFootnote 28 around the world to staff. One-quarter (26%) also highlighted the need for enhancing or standardizing processes involving Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), such as the steps for obtaining missing information on referrals in a timely manner. A minority of analysts (16%) also indicated a lack of consistency in procedures across GeoDesks, including the thresholds applied for writing inadmissibility recommendations (i.e., what information is sufficient to initiate the process). In addition, SOPs do not fully articulate how analysts are to maximize the use of high-quality, open source information in such a way that it will serve as a solid basis for a recommendation. Relying on open source (versus classified) information helps ensure procedural fairness, although this is not always feasible.

Training of National Security Screening Division analysts

Finding 11: NSSD analysts received a wide variety of job-specific training; however, some gaps were identified.

Security screening processing is knowledge and information-intensive. NSSD analysts are required to navigate numerous databases; to acquire, absorb and apply information to critically assess applications for inadmissibility concerns; and to make defensible judgments in a timely manner. The nature of analysts’ work requires a significant amount of training at the onset, as well as continuing professional development and guidance.

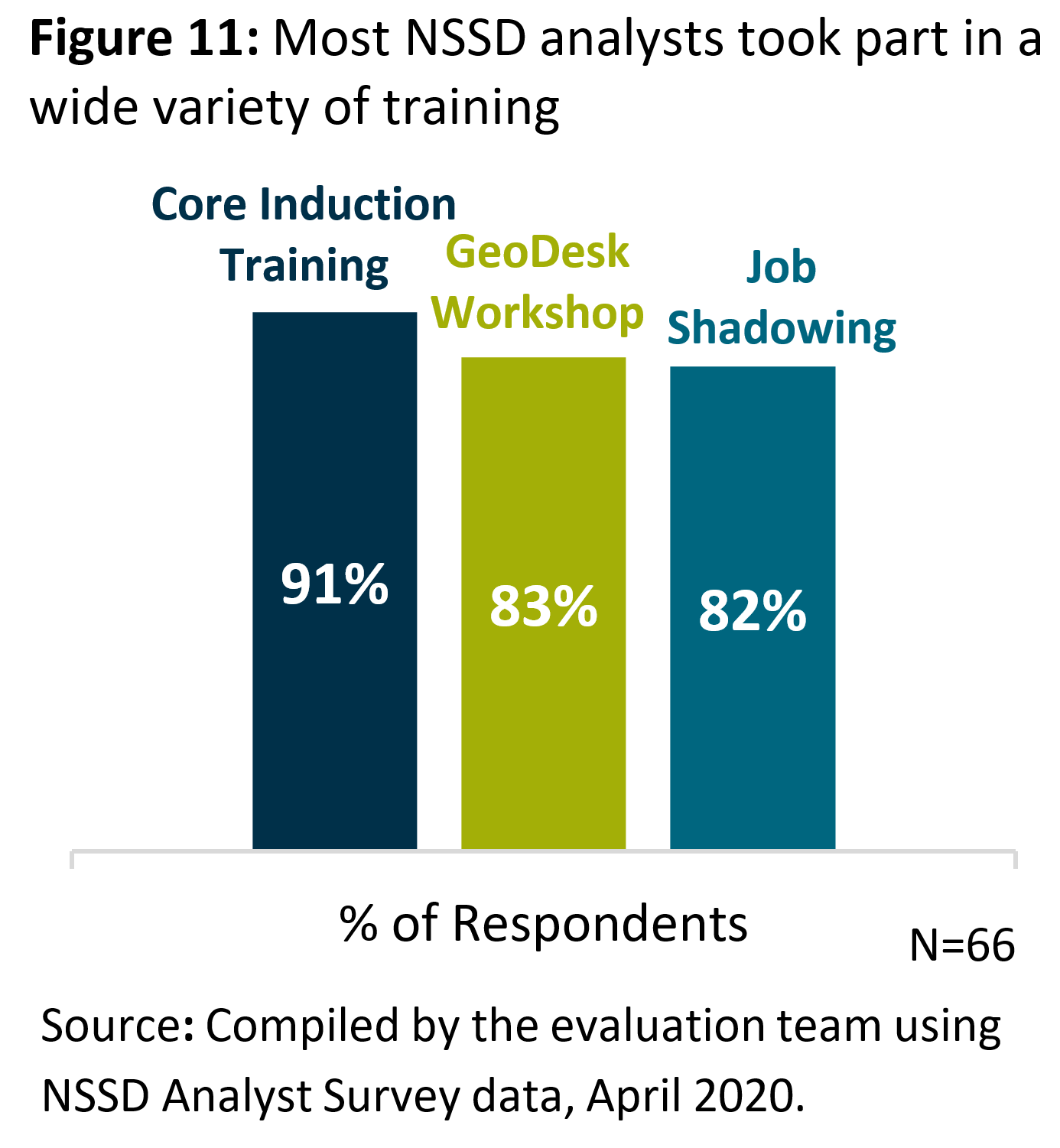

NSSD provides substantial training to its analysts, particularly upon joining the Division. The week-long Core Induction Training (CIT), which includes in-class and on-the-job training, is offered on a regular basis and when significant recruitment has taken place. Team Leads are responsible for providing mentoring and job shadowing opportunities both during induction and afterward, which are considered essential to building analysts’ skills and expertise. Occasional GeoDesk/regional-specific training is also provided by subject matter experts. A large proportion of analysts reported participating in all these types of training (see Figure 11). In addition to legal training that is part of the CIT, NSSD analysts have the opportunity to participate in regular legal training sessions provided by the Department of Justice Canada (JUS) and the Canada Border Services Agency’s (CBSA) Litigation Management Unit (LMU).

Text version: Figure 11

Figure 11 shows that most NSSD analysts took part in a wide variety of training:

- 91% took part in Core Induction Training

- 83% took part in GeoDesk Workshop Training

- 82% took part in Job Shadowing

Source: Compiled by the evaluation team using NSSD Analyst Survey data, April 2020.

Training on recognizing inadmissibility under Immigration and Refugee Protection Act

According to the NSSD analyst survey, almost all NSSD analysts (97%) reported that they had received specific training, coaching or job shadowing on recognizing inadmissibility under sections 34 and 35 of Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA); 94% had received specific training for section 37. Approximately 4 in 10 analysts indicated they had received JUS training specifically focusing on each section of IRPA, while one-fifth of analysts had also taken advantage of the CBSA LMU consultations on determining IRPA inadmissibility.

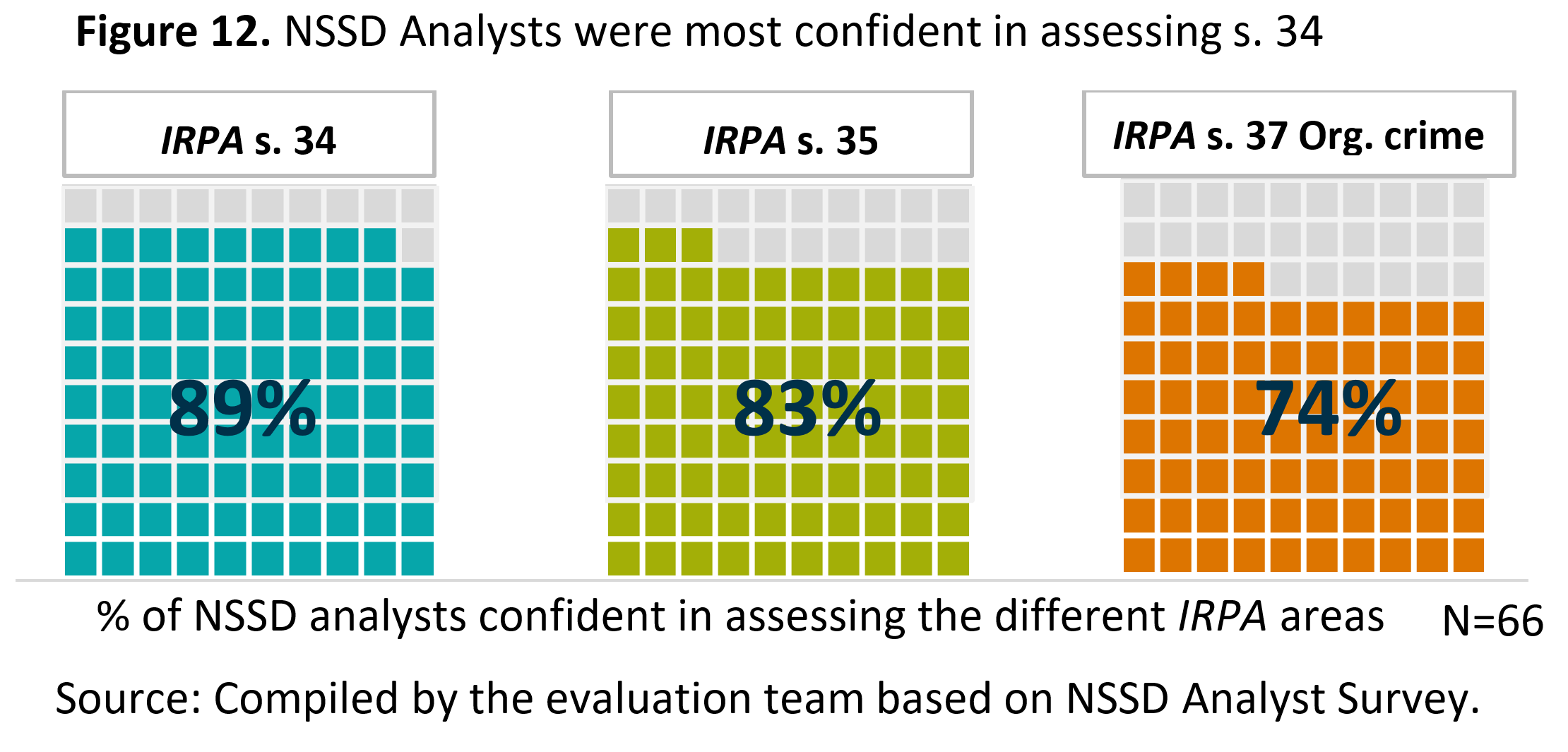

Generally, NSSD analysts reported feeling confident in assessing applicant’s potential inadmissibility. As can be seen from Figure 12, they were most confident in assessing inadmissibility based on IRPA section 34 (89%) and somewhat less confident with regards to IRPA section 37 (74%). [redacted]

Text version: Figure 12

Figure 12 shows the percentage of NSSD analysts confident in assessing against different sections of IRPA:

- 89% of NSSD analysts reported feeling confident in assessing IRPA s. 34

- 83% of NSSD analysts reported feeling confident in assessing IRPA s. 35

- 74% of NSSD analysts reported feeling confident in assessing IRPA s. 37 related to organized crime

Overall, NSSD Analysts were most confident in assessing against s. 34 or IRPA.

Source: Compiled by the evaluation team based on NSSD Analyst Survey.

Training gaps

Despite the variety of training available to NSSD analysts, there are areas where additional training or guidance is needed. Most prominently, NSSD analysts have experienced challenges when trying to access Privy Council Office (PCO) intelligence-related courses, which are highly relevant to analysts’ work. These courses have limited seats and are costly. Seat allocation occurs at the Agency level, and employees in the regions tend to be prioritized, with very few NSSD analysts obtaining seats (only 12% of surveyed NSSD analysts reported having taken a PCO course). In response, NSSD developed a National Training Standard (NTS), which made certain PCO courses mandatory for junior (FB-02) and senior (FB-04) NSSD analystsFootnote 29. However, the NTS on its own is unlikely to ensure access to these intelligences courses due to their limited availability in general.

Furthermore, as NSSD analysts reported less confidence in assessing applicant’s inadmissibility based on IRPA section 37 relative to other sections, there is a need for more comprehensive training on recognizing inadmissibility concerns related to organized criminality.

Quality and quantity of referrals

Security screening indicators as a tool to manage referrals

The quality and quantity of referrals sent to NSSD is largely determined by IRCC officers who review temporary residence (TR) and permanent residence (PR) applications and decide who to refer. Their decisions are guided by security screening indicators, which assist IRCC officers in identifying applicants who may be inadmissible to Canada in light of security concerns. The indicators cover [redacted] that could indicate inadmissibility and ultimately lead to an applicant being found inadmissible based on security grounds.

Since August 2018, some security screening indicators have been updated into new thematic indicator packages. [redacted], with indicators reflecting potential concerns associated with [redacted]. As of August 2020, there were 16 valid thematic indicator packagesFootnote 30. The goal is to develop thematic indicator packages [redacted], to ensure that 95% of all TR and PR applications are screened using thematic indicators.

The new thematic indicator packages seek to fulfill two broad objectives:Footnote 31

- To improve the quality of application referrals made by IRCC and

- To reduce the number of unnecessary application referrals made by IRCC

When the new thematic indicators were released, the key distinguishing feature was the discretion accorded to IRCC officers. Unlike the original indicators, the new packages allowed them to use their own judgement and consider all the criteria to determine whether further screening is required or whether they have enough information to approve or reject application without the input from security screening partners. The original indicators continue to be used by IRCC to screen applicants from countries for which no new thematic indicators exist; however, since December 2019, the original indicators no longer require mandatory referralsFootnote 32. For more on IRCC officers’ use and assessment of security screening indicators, see Appendix J.

Assessing referral quality in a comprehensive manner remains a challenge for the Program. The quality of referrals could potentially be measured by the proportion of incomplete referrals or unnecessary referrals (i.e. applications that could have inadmissibility determined by IRCC without security screening from partners). However, currently the INSS program does not consistently track the occurrence of incomplete or unnecessary referralsFootnote 33. Therefore, the extent to which referrals did not meet expectations in terms of quality remains unclear. IRCC maintains that, after a number of recent consultations with NSSD on this issue, few referrals were identified by NSSD as having not been warranted.

The impact of new thematic indicators on referrals

Finding 12: The new thematic indicators have the potential to improve security screening referrals, but as yet this impact has not been realized.

Security screening indicators are intended to support IRCC officers in making informed, quality referrals to security screening partners and to reduce the number of unnecessary referrals. However, as of the end of the evaluation period, the usage of the new indicator packages had yet to be tracked, so the evaluation team was not able to fully assess the use or effectiveness of these indicators.

Upon release of the new thematic indicators, the IRCC did not have a means to systematically record which indicator(s) triggered each referral, leaving NSSD with no indication as to whether the new indicators were being applied and whether they were being applied correctly and consistently. While the need to record the usage of new indicators was recognized soon thereafter, the indicators are classified as Secret/Canadian Eyes Only, [redacted]. Therefore, partners had to first design a numbering system to be able to refer to these indicators without actually revealing their contentsFootnote 34. Updates to the CBSA’s and IRCC’s tracking systems are underway, and should be in place by June 2021.

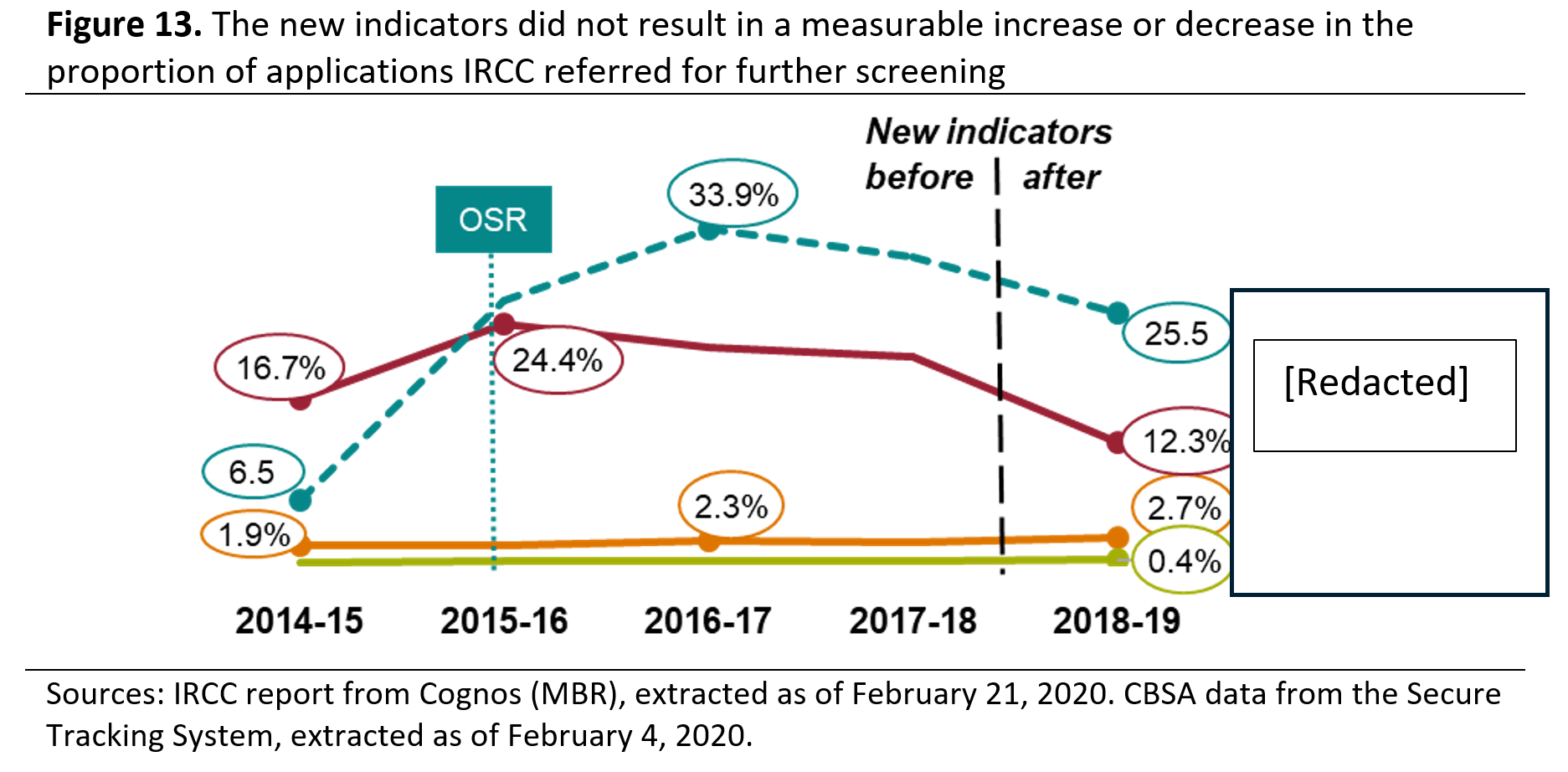

The impact of the first thematic indicator packages on the proportion of applications referred

In the absence of specific metrics to determine whether the objectives of the new thematic indicators had been achieved, the evaluation focused on comparing the quantity of referrals received by NSSD before and after the implementation of the first four packagesFootnote 35. The goal was to determine if the implementation of the new indicator packages caused IRCC officers to refer a larger or smaller proportion of applicants [redacted]Footnote 36.

Overall, the percentage of applications referred after the thematic indicators were introduced appeared to follow [redacted] referral trend. This suggests that the implementation of the new thematic indicators did not have an impact on the proportion of referrals submitted to NSSD, at least until March 2019 (the end of the evaluation period). Specifically, as can be seen in Figure 13, the proportions [redacted] applicants referred for screening were on a downward trend since at least 2016 to 2017. This finding is consistent with the overall decrease of new referrals for [redacted] applicants after the Operation Syrian Refugee (OSR) surge, as well as a change in screening indicators used for [redacted]. Meanwhile, the percentage of referrals for applicants from [redacted], historically very low, increased marginally, with no noticeable change after the new indicators were applied.

Text version: Figure 13

Figure 13 shows that the new indicators did not result in a measurable increase or decrease in the proportion of applications IRCC referred for further screening.

| Year | Proportion of referrals submitted to NSSD Country: [Redacted] |

Proportion of referrals submitted to NSSD Country: [Redacted] |

Proportion of referrals submitted to NSSD Country: [Redacted] |

Proportion of referrals submitted to NSSD Country: [Redacted] |

| 2014 to 2015 | 1.9% | 0.4% | 6.5% | 16.7% |

| 2015 to 2016 (OSR) | 0.4% | 26.6% | 24.4% | |

| 2016 to 2017 | 2.3% | 0.4% | 33.9% | |

| 2017 to 2018 | 0.4% | 20.9% | ||

| 2018 to 2019 | 2.7 | 0.4% | 25.5% | 12.3% |

Sources: IRCC report from Cognos (MBR), extracted as of February 21, 2020. CBSA data from the Secure Tracking System, extracted as of February 4, 2020.

The impact of new indicators on the use of discretion and on reducing unnecessary referrals

In the context of the new thematic indicators, unnecessary referrals are either those that NSSD would not expect to receive based on IRCC officers using their greater discretionary power to not refer, or are referrals that did not correspond to relevant thematic indicatorsFootnote 37Footnote 38. According to IRCC data, IRCC officers did not start exercising greater discretion afforded to them with the new indicators. An analysis of the number and percentage of TR applicants rejected by IRCC officers in their initial assessment (i.e., without referring the applications to security partners) based on security inadmissibility indicated no significant change following the introduction of the new indicators.

Conversations with stakeholders coupled with survey results identified several key reasons why IRCC officers may be hesitant or unable to exercise their new discretionary power to not refer:

- Lack of timely, sufficient training on the new thematic indicators

- Very few applicants are believed to honestly declare clear inadmissibility information such as a membership in a group engaging in terrorist activities or organized criminality

- IRCC officers feel more comfortable having the opinion of security partners when making a decision on inadmissibility, particularly given the consequences of such a decision

- Decisions concerning inadmissibility based on security grounds are heavily scrutinized, and IRCC officers prefer, if possible, to reject an application based on other grounds and

- Some long-standing IRCC officers continue assessing applications under the former approach of simply referring without necessarily relying more on their own judgement

In terms of reducing these unnecessary referrals, there is currently no systematic way to identify which referrals were previously considered unnecessary and therefore whether the overall number of unnecessary referrals decreased with the introduction of the new thematic indicators. NSSD, in collaboration with IRCC, undertook several initiatives to assess the effectiveness of the new thematic indicators, but the results were inconclusive (see Appendix F). There were also measures introduced under the BRTAP (see Backlog reduction and transformation action plan) that specifically aimed at reducing low-risk referrals. According to NSSD management, BRTAP measures, such as no longer referring low-risk homemakers, had a noticeable impact on reducing the number of unnecessary referrals.

Finally, there is no monitoring in place to determine the extent to which applicants are not being referred to NSSD despite presenting potential security concerns (through applying the security screening indicators or otherwise). This is especially important given that the previous version of indicators used by IRCC officers for TR and PR applications contained indicators which triggered mandatory referrals, whereas decisions to refer applicants are now discretionary.

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada officers' use and assessment of the indicators

In order for security screening indicators to be effective, they need to be readily accessible and regularly used by authorized IRCC officers. Security screening indicators are classified Secret/Canadian Eyes Only, which requires that they be stored securely in locked cabinets in secluded areas of the mission. Therefore, their retrieval may be onerous and thus discourage officers from consulting them when required. Nonetheless, according to survey results, most (79%) IRCC officers working at missions overseas did not report experiencing issues with accessing the indicatorsFootnote 39. The survey further indicated that most officers (72%) consult the indicators on a regular basis and generally find them quite useful (78%). The IRCC officers who did not find the indicators to be particularly useful cited the following challenges:

- indicators are broad, making it difficult to apply them (38%)

- indicators require information on the applicant that is not easily accessible (21%) and

- there are a large number of indicators to be consulted (17%)

Involvement of locally engaged staff in processing applications

IRCC missions abroad hire local employees who typically are not Canadian citizens, known as locally engaged staff (LES)Footnote 40. The roles and responsibilities of LES vary by mission, ranging from clerical support to decision-making. As per the IC Manual – Chapter 1, LES may be tasked with preparing and transmitting security screening requests only when the request does not contain any classified or sensitive material (clerical support), whereas IRCC officers review TR and PR applications to ensure they are complete and to make admissibility and eligibility decisions (which involves accessing the security screening indicators)Footnote 41. Any LES who are not Canadian citizens and not in possession of a valid secret security clearance are not authorized to view the security screening indicators that are used in the initial screening of applications. However, according to the evaluation survey, 16% of IRCC officers (located in 15 different IRCC visa offices) indicated that LES at their missions were engaged in the actual processing of applications. Furthermore, 4% (6 individuals, located in 4 different IRCC missions) specified their LES were using the security screening indicators. Fundamentally, the involvement of LES in processing applications, even if not widespread, poses specific risks and challenges to the integrity of the security screening process. LES who screen applications without consulting the security screening indicators do not have all the information they need to determine potential security concerns, while non-Canadian LES who access the indicators are committing a security violation.

Consideration: The Program is encouraged to engage its INSS partners on the involvement of LES in the processing of applications at missions abroad, to ensure they are performing tasks in accordance with operational policy and procedures.

Training provided to Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada officers

Finding 13: While most IRCC officers had received indicator training from the NSSD and found it useful, additional guidance on assessing inadmissibility is still required.

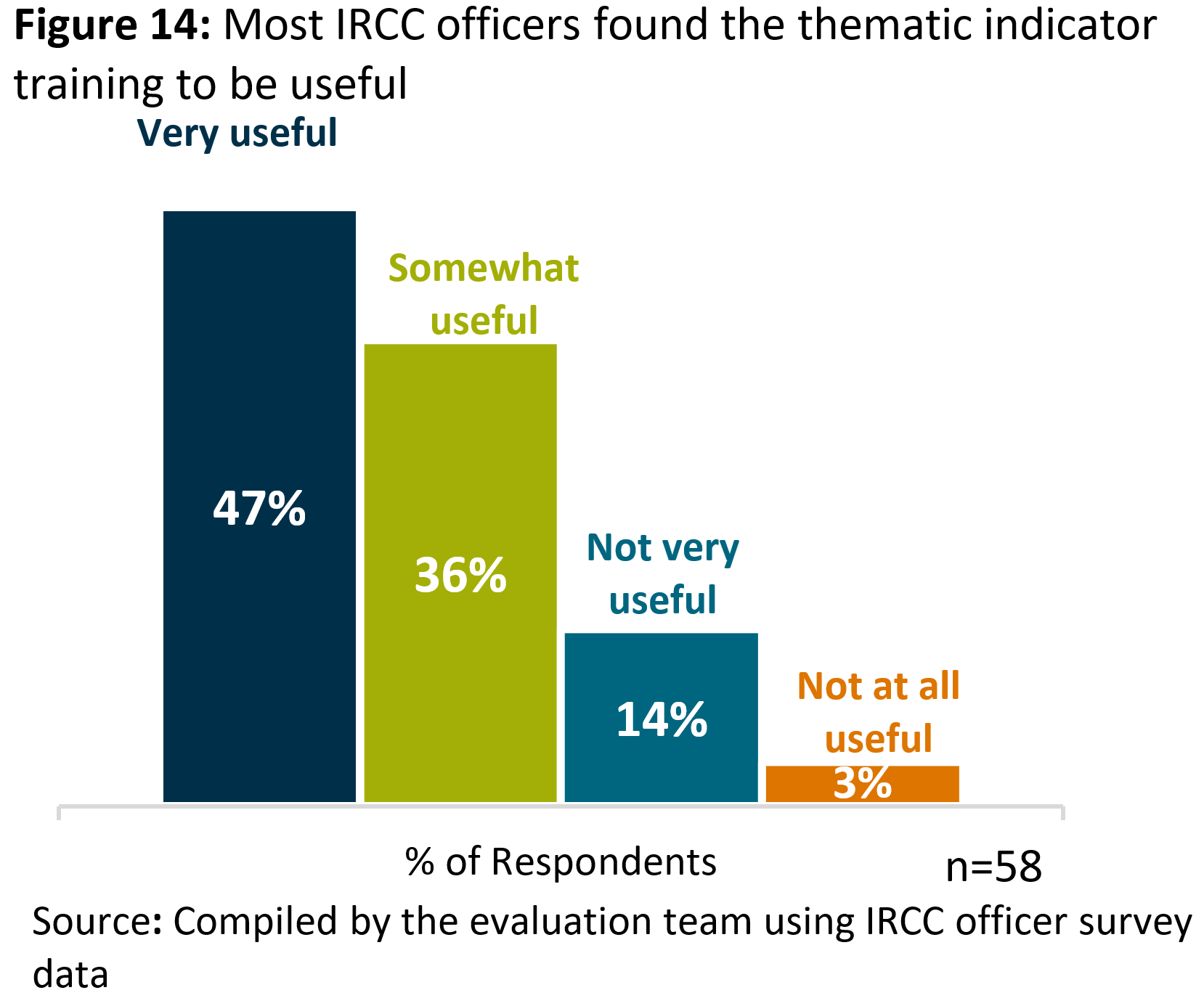

In 2019, NSSD subject matter experts provided tailored thematic indicator training sessions to IRCC officers, and in some cases to LESFootnote 42, at several overseas missions. The ultimate goal was to increase the quality of referrals from IRCC missions. The vast majority (88%) of IRCC officers who responded to the survey had experience with using the new thematic indicators. Of those officers, half indicated they had received thematic indicator training given by NSSD staff. Most (83%) of this subset of officers found the training very or somewhat useful (see Figure 14).

Text version: Figure 14

Figure 14 shows that most IRCC officers found the thematic indicator training to be useful:

- 47% found the training to be very useful

- 36% found the training to be somewhat useful

- 14% found the training to be not very useful

- 3% found the training to be not at all useful

Source: Compiled by the evaluation team using IRCC officer survey data

NSSD management views the training of IRCC officers as key to receiving high-quality referrals, including only referrals that warrant screening. While the surveyed IRCC officers considered the training useful, there is little data available to demonstrate the impact of the training on the number and quality of referrals sent to NSSD. In addition, this training is costly for NSSD in terms of the staff time and travel costs. Therefore, before continuing further with this training, NSSD should first collect more data to demonstrate its actual impact.

Overall, almost 40% of IRCC officers felt they required further training and/or guidance to support them in assessing applicants’ inadmissibility on security grounds, with the most frequently cited areas being the regional context (e.g. changing social, economic, or political conditions; 36%) and ongoing/refresher training on indicators (34%).

Incomplete referrals from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada missions and CBSA regions

NSSD stakeholders indicated that a significant number of referrals were received without all the required information, which impacts the Division’s ability to issue recommendations within the service standard performance target. From the IRCC’s perspective, the lack of guidance and definitions as to what constitutes a complete referral up until recently was a contributory factor. If a referral is incomplete, NSSD has to follow up with the IRCC officer at the mission (or regional CBSA officer in the case of refugee claims) to request the missing information, with the time taken to obtain the information counting towards NSSD’s processing time.

An analysis of the case management data indicated that the proportion of referrals submitted to NSSD which lacked all the required information declined over the evaluation period, except for TR referrals. While most IRCC missions sent complete referrals, some missions were submitting significant proportions of referrals that were incomplete. Between 2014 to 2015 and 2018 to 2019, one quarter (26%) of Chandigarh’s referrals were incomplete, as were 18%-19% of referrals from Guangzhou and Ho Chi Minh missions. Among the CBSA regions, 16% of the GTA’s referrals were incomplete, as were 13% of those submitted by the Southern Ontario Region. While the proportion of incomplete referrals decreased over time, wait times for receiving missing information increased. On average, NSSD waited about 1-2 weeks longer for partners to provide missing information in 2018 to 2019 than they did in 2014 to 2015. However, the data also showed that, overall, incomplete referrals were processed faster than those received with all the required information (for more information, see Appendix E).

NSSD has been working with IRCC to address the issue of incomplete referrals at the specific missions of concern. In this context, IRCC officers have now been provided with the required guidance through the existing IRCC Program Delivery Instructions and the IRCC has also launched a pilot project targeting these specific missions to reduce incomplete referrals.

Collaboration with partners and within the CBSA

CBSA, CSIS and IRCC work in partnership to deliver the INSS. The extent to which partners work together effectively significantly influences the overall integrity and success of the security screening continuum and the ability to achieve government-wide outcomes.

Working relationships among federal partners

Finding 14: NSSD has effective working relationships overall with IRCC and CSIS. The involvement of Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) in the security screening process would be highly beneficial.

The roles and responsibilities of security screening partners are clearly articulated in multiple documents such as IRPA, the bilateral Memoranda of Understanding (MoU) between partners, and program policies and proceduresFootnote 43. While partners generally shared the view that the roles and responsibilities were clear, some areas requiring further improvement were identified. Notably, the lack of a trilateral MoU, during the period under evaluation, was a recognized issue, as was the lack of involvement of the RCMP in the security screening process.

Trilateral MoU between the CBSA, IRCC and CSIS

Stakeholders from all three partner entities felt that the new trilateral MoU would benefit the security screening process by defining and describing the specific tasks fulfilled by each partner, and the interdependencies between partners’ key activities. Developed at the end of 2020 to 2021, the MoU can be leveraged by partners to bring improvements to several areas, by:

- Assigning responsibilities for performance measurement across the security screening continuum

- Establishing a monitoring mechanism to determine whether all applicants who should be referred for screening are being referred

- Supporting collaboration to deliver regular training to IRCC officers and

- Adopting a whole-of-government approach to setting service standards

The intention to develop the MoU was approved by all three organizations in mid-2020; it was in the approval process at the time of the writing of this report.

Missing intelligence from the RCMP to assess organized criminality

The RCMP is notably absent from the security screening process. Until about 10 years ago, the RCMP used to be involved in screening activities, and provided valuable assistance in determining inadmissibility due to organized criminality. Security screening partners, and NSSD in particular, have agreed that re-engaging RCMP should be considered. A planned tabletop exercise between the NSSD and RCMP was scheduled in early 2020, but was postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Following this exercise, the NSSD and partners will be better informed on the opportunities for collaborating with the RCMP, and the implications, benefits and drawbacks this would have. There may also be other options to obtaining more information and intelligence to support NSSD analysts’ assessments of inadmissibility due to organized criminality, besides re-engaging the RCMPFootnote 44.

Communication between NSSD and its partnersFootnote 45

During the evaluation period, in NSSD’s opinion, effective mechanisms were in place to facilitate communication between NSSD and its security screening partners. Several senior management oversight committees met regularly and provided partners with a platform to discuss program performance and challenges. Such oversight committees are regarded as central to early identification of issues that could impact the effectiveness of the security screening process, such as surges in PR or TR applications from specific regions.

Inter-partner improvement initiatives with Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

During the evaluation period, a number of joint initiatives were implemented to improve program delivery. These included inter-departmental working groups to develop and update screening indicators, pilot studies to assess the use of screening indicators, and knowledge sharing between NSSD analysts and IRCC officers (for more information, see Appendix F). While these initiatives sought to fulfill various needs across the security screening continuum, most of these efforts focused on the initial assessment of applications by IRCC officers to ensure that IRCC officers are referring only applicants who should be screened.

Interdependencies with Canadian Security Intelligence Service

Applications referred for IRPA s.34 inadmissibility concerns have to be screened by both NSSD and CSIS. Between April 2014 and March 2019, [redacted] of all referrals fell into this category and were screened by both partners. While NSSD and CSIS receive and assess each referral simultaneously and follow the same service standard, NSSD must wait for CSIS’ input before finalizing and issuing the recommendation. Therefore, NSSD’s ability to meet the service standards depended, to a certain degree, on CSIS’ ability to complete its screening on time. The average number of calendar days CSIS took to process referrals increased over the evaluation period for all three business lines, but particularly for PR referrals. CSIS’ timelines for PR screenings increased more than 15-fold between 2016 to 2017 and 2018 to 2019. As of March 31, 2019, the end of the evaluation period, 52% of NSSD’s inventory (5,790 referrals) comprised cases that were already processed by NSSD, but were awaiting CSIS’ assessment.Footnote 46Footnote 47

Importantly, NSSD and CSIS have different responsibilities; CSIS provides intelligence on security concerns, while NSSD is the partner that develops the admissibility recommendation. Further, the two partners use different thresholds and investigative techniques for their assessments, as established by their relevant Acts. NSSD applies reasonable grounds to believe (as determined by IRPA), while CSIS uses reasonable grounds to suspect (as established by the Canadian Security Intelligence Service Act). Since CSIS’ threshold is lower than NSSD’s, information gathered during CSIS’ screening may not be sufficient for NSSD to find the applicant inadmissible. For this and other reasons, NSSD and CSIS formally launched the Fusion Centre Initiative in 2018 to 2019, whereby NSSD analysts from three of the four GeoDesks worked in person alongside their CSIS counterparts once or twice a week. This arrangement has allowed for in-person discussions of specific cases, ensuring that CSIS provides the useful and usable information to NSSD.

Collaboration between National Security Screening Division and CBSA regions in screening refugee claimants

Refugee claimants are screened through the Front-End Security Screening (FESS) process, which is conducted by NSSD with the support of the regional hearings and investigations units (see Front-end security screening of refugee claimants and Appendix H for more information on areas of overlap/duplication). The major difference in the security screening performed by each entity is that NSSD screens all adult refugee claimants, while regions only conduct screening and investigations on selected individuals, most often those who were flagged by regional triage or (less frequently) during refugee claim intake.

If the NSSD finds serious security concerns, it will send the file to the regional investigations unit and hearings unit for further investigation. In practice, however, regional investigations into potential concerns posed by refugee claimants and preparation for Immigration and Refugees Board (IRB) hearing often commence before NSSD completes its screening and has sent the result to the region. Because regions do not wait for NSSD’s screening result and use their own triage criteria, they may also conduct investigations on refugee claimants who were screened as favourable by the NSSD.

Finding 15: There is a lack of coordination and communication between NSSD and regions, resulting in misalignment between their respective screening activities.

The NSSD and the regions operate more or less independently, with each collecting data from different sources for their own purposes. Some NSSD analysts expressed frustration over the lack of coordination between NSSD and regional screening activities. Specifically, they felt that NSSD’s recommendations were being ignored by regional CBSA officers, who instead relied on their own screenings. Regional hearings and inland enforcement officers (IEOs), on the other hand, were not clear on what was involved in NSSD’s screening process, nor how reliable it was. Regions reported typically receiving only the result of NSSD’s screening (e.g. favourable or non-favourable) and limited information in the case of non-favourable screenings, although NSSD maintains that they send a full brief when the result is non-favourable. As a result, regions often conduct some or all of the same checks, including a scan of social media.Footnote 48

In regions with fewer refugee claimants and/or a higher processing capacity, investigations may begin immediately after the regional triage stage, and may conclude before NSSD is finished its screening. Some regional representatives argued that, in such instances, the NSSD screening result is received too late and does not add value. This was particularly the case during the height of NSSD’s backlog in 2017 to 2018. In one region, stakeholders felt that, during the backlog period, the quality of NSSD screenings was lower or less predictable, which led some regional hearings and IEOs to lose trust in NSSD’s security checks. Despite improvements in quality and processing (as perceived by these stakeholders), some officers continue to rely on their own screenings rather than on those provided by NSSD.

The lack of coordination has been highlighted in previous studies (2018 CBSA Hearings Program Evaluation; 2017 Deloitte review of the FESS process). The areas of overlap identified by the Deloitte study were reviewed and updated through stakeholder consultations as part of this evaluation, and are listed in Appendix H.

While communication channels between NSSD and regions exist, they are used on an ad hoc basis, either by NSSD to request that regions collect additional information from claimants or by the regions to inquire about the status of a security screening for which an IRB hearing has already been scheduled. There is no regular communication between NSSD and the regions to provide updates on the screening processes, to exchange information on trends or best practices, or to better understand each other’s roles and responsibilities and operating procedures. There is also a lack of strategic engagement between NSSD and regional leadership. Regions further identified the need to share tools and/or receive more support from NSSD to access key resources such as subscription databases to query individual claimants.

Data systems and IT infrastructure

Effective and efficient processing of security screening referrals across the security screening continuum is dependent on the capacity of partners to transfer data from one organization to another, and to be able to share information quickly and reliably. Considering that each organization uses a different case management system, systems interoperability is a key factor in ensuring effective screenings. In addition, the NSSD’s own IT infrastructure plays a major role in how quickly the Division is able to process referrals, specifically in times of high workload.

Data systems used by partners

Each security screening partner uses its own case management system: IRCC uses the Global Case Management System (GCMS), NSSD uses the Secure Tracking System (STS), and CSIS has its own secure system. However, as the activities of IRCC, NSSD, and CSIS happen in a continuum, there is a need for a smooth, timely, and efficient flow of data and information between the different systems.

Finding 16: While the lack of interoperability among partners’ data systems has been a long-standing issue, NSSD analysts felt they had the information they needed to perform screenings.

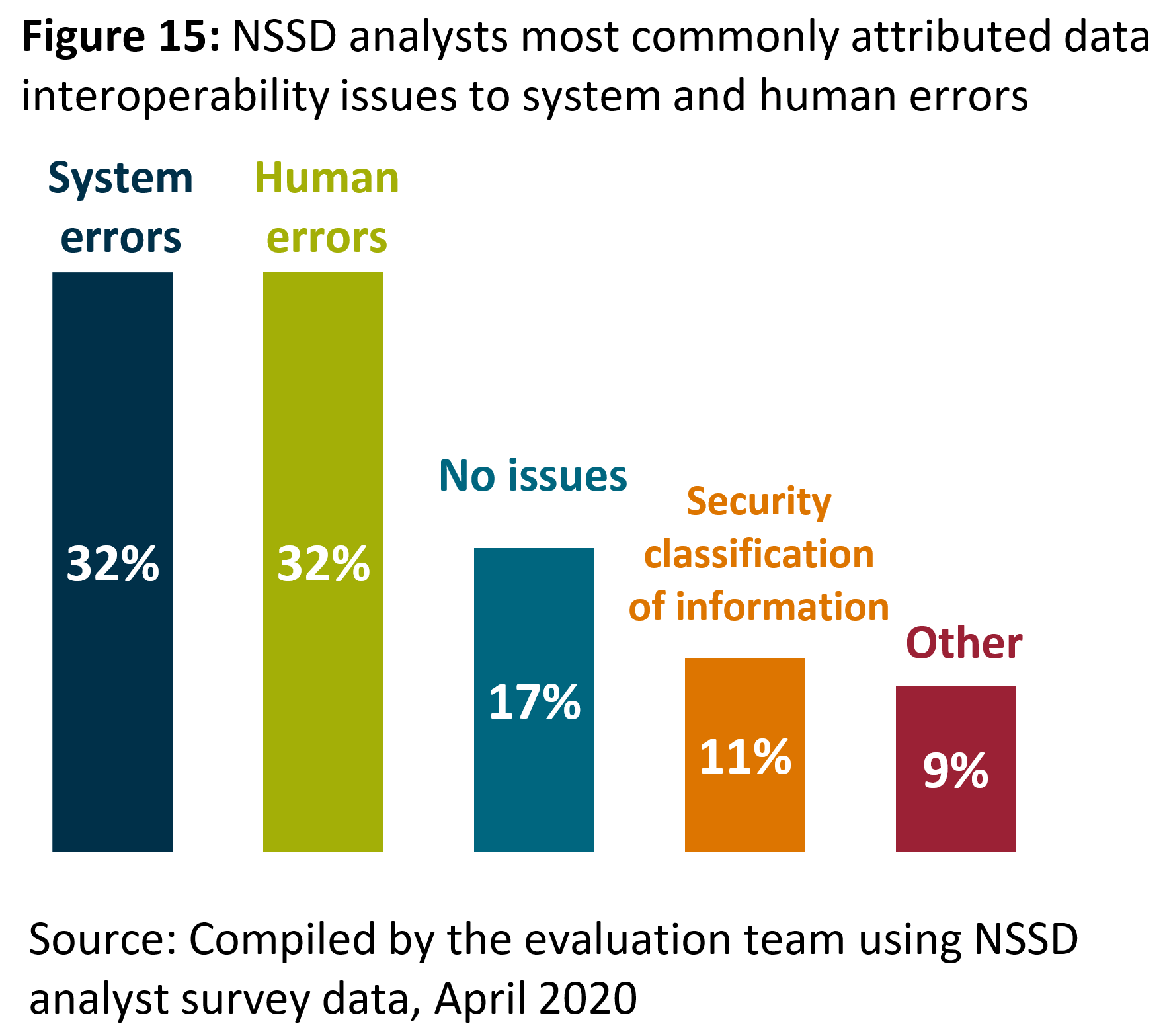

As each data system used in the security screening process is primarily designed to meet the objectives of the organization that uses it, functions are not necessarily designed to enable a smooth transfer of information between systems. According to the survey results, system and human errors were the most common causes of incomplete data transfer, cited by 64% of NSSD analysts (see Figure 15).

Text version: Figure 15

Figure 15 shows that NSSD analysts most commonly attributed data interoperability issues to system and human errors:

- 32% of analysts attributed data interoperability issues to system errors

- 32% of analysts attributed data interoperability issues to human errors

- 17% of analysts indicated no issues with attributed data interoperability

- 11% of analysts attributed data interoperability issues to security classification of information

- 9% of analysts attributed data interoperability issues to other factors

Source: Compiled by the evaluation team using NSSD analyst survey data, April 2020

While some system upgrades have been put in place, several challenges remain, including:

- Data transfer is one-time in nature. NSSD analysts have to manually search GCMS to verify if any changes to the file have been made by IRCC between the time of the referral and when NSSD finishes its screening

- IRCC attachments are not readable by the other systems. IRCC’s attachments (e.g. interview notes in a PDF format) are not readable by the NSSD’s and CSIS’ data systems, and therefore require manual review to be analyzed. [redacted]Footnote 49

- Current systems do not record instances of faulty information transfer. Quality Assurance (QA) on data transfer and integrity across the systems remains limitedFootnote 50. Although partners are aware of specific issues, the extent to which data transfer errors occur is unknown

Issues with data transfer and interoperability of partners’ data systems have been documented previously, including in the 2011 OAG report on issuing visas, the 2017 internal audit of OSR, and the 2019 OAG report on processing asylum claims. However, according to survey results, most NSSD analysts felt, at least to some extent, that data transfer among the different systems was both accurate (86%) and prompt (77%)Footnote 51.

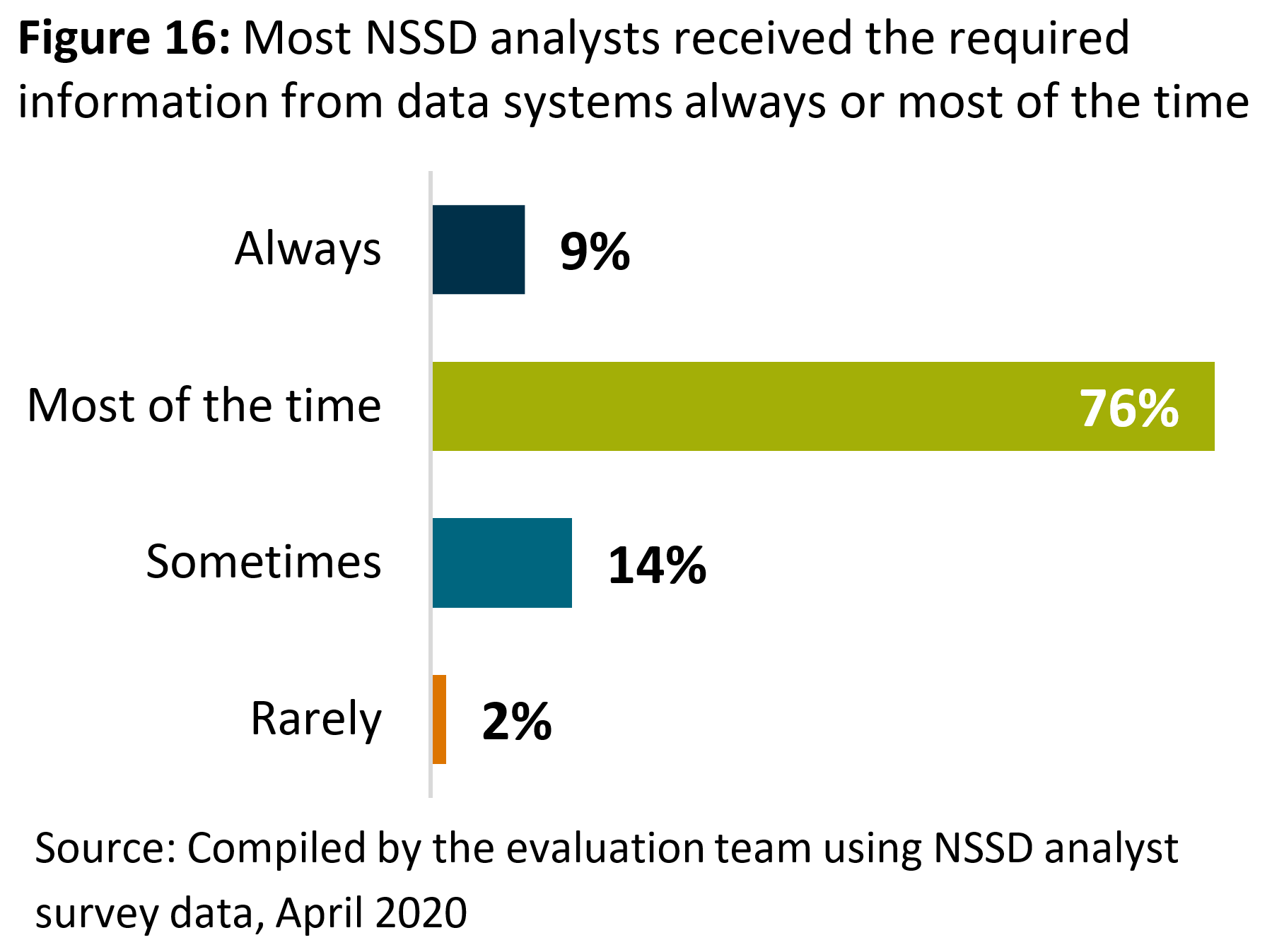

In fact, despite system challenges, most NSSD analysts (85%) indicated they always or most of the time received the information they needed from data systems to be able to conduct security screenings (see Figure 16).

Text version: Figure 16

Figure 16 shows that most NSSD analysts received the required information from data systems always or most of the time:

- 9% indicated always receiving the required information from data systems

- 76% indicated receiving the required information from data systems most of the time

- 14% indicated sometimes receiving the required information from data systems

- 2% indicated rarely receiving the required information from data systems

Source: Compiled by the evaluation team using NSSD analyst survey data, April 2020

Security screening automation initiative

Throughout the evaluation period, NSSD’s screening was largely dependent on a number of manual tasks performed by analysts. Manual processing not only limits the processing ability of the Division but is also more prone to human error. To this end, the CBSA is currently pursuing a Security Screening Automation (SSA) initiative.

Finding 17: Automation is the future vision of the Program, but has associated risks and is not expected to be fully implemented until fiscal year 2023 to 2024 at the earliest.

The SSA initiative is a $40-million investment that will automate NSSD’s triage function “by enabling a systematic review of screening and threat indicators against each application”Footnote 52. The objective is to develop and deploy automation to allow NSSD to refocus analysts’ efforts on cases with higher risk profiles. The specific goals are to achieve greater system and indicator precision, to promote adaptation in screening to changing country and regional conditions, to reduce human error, and to generate more objective recommendations.

The SSA is scheduled to be implemented over a three-year period between fiscal years (FY) 2020 to 2021 and FY 2023 to 2024 and will fundamentally change the NSSD’s business model. As with any other large-scale IT project, there are numerous risks, which are being monitored and managed to ensure the achievement of project outcomes. These risks include ongoing funding that has yet to be secured for the project maintenance after its initial roll-out, potential IT procurement delays, and dependencies between SSA and other initiatives, such as the IRCC-led Asylum Interoperability Project. The SSA includes plans to integrate text analytics for subjective risk assessment by leveraging a Cloud-based advanced analytics platformFootnote 53. It will be important to ensure that this capability is functioning as intended before NSSD fully switches to the new automated environment, to eliminate the risk of clearing cases where derogatory information is only included in unstructured text. Finally, once implemented, the SSA may increase pressure on CSIS to finish its assessments faster, since NSSD will be able to conduct its screening activities faster. If CSIS is not able to keep pace, NSSD will ultimately see backlog growth.

Note: In October 2019, NSSD began pursuing the acquisition of Robotic Process Automation software as an interim solution to help bridge the current systems gaps. Robotic Process Automation is supposed to speed up the screening process, allowing NSSD officers to focus more on analysing information and determining risk.

- Date modified: